What is Natural? : Shifting Baselines in Wildlife Conservation

By Dr. Andrew Baker

Most people are familiar with the diverse threats to the conservation of Earth’s natural wildlife and landscapes. What was once unthinkable has now become banal, a litany of deforestation, habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change, all driven by the expansion of our human population into the planetary biosphere. In the face of these threats, we have made increasing efforts to protect wild landscapes, save species, and appreciate the linked nature of humans with their ecosystems. This has helped us recognize that intact ecosystems are generally much better at providing the goods and services which we covet and value.

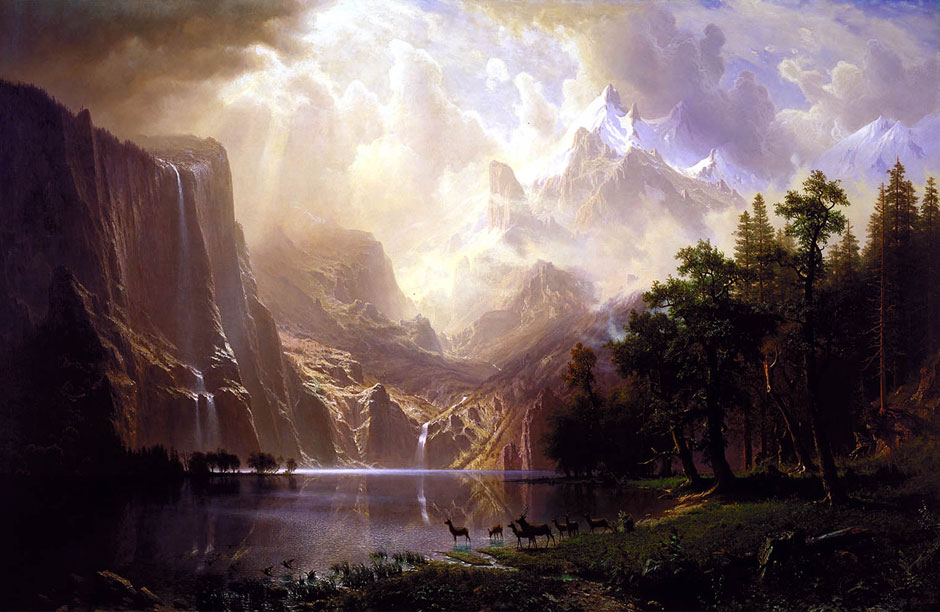

Yet there is one threat to the conservation of nature that few people are aware of, one so insidious that it may represents the single largest threat to natural landscapes and pristine wildlife because it thwarts our greatest ambitions before they even germinate in our mind as a desired conservation outcome. For almost two decades, scientists have had a name for this threat: the “shifting baseline syndrome”. Most people’s perception of the natural state of ecosystems is grounded in their personal experience, often formed during their earliest exposure to nature, during childhood or early adulthood. This impression often defines the target baselines for conservation efforts, because earlier and more intact states are unknown and unimagined.

My own baseline for defining “nature” stems from growing up amid pastoral landscapes in the south of England. It is set in a hedgerow ecology of patchwork fields and grassy hillsides punctuated by meandering rivers. Yet, none of this accurately represents the natural state of the British Isles, which were heavily forested less than 400 years ago and have been dense woodland for most of human history. Consequently, my perception of the threat to the natural environment of the British Isles is limited to the changes I have seen within my lifetime: the incursion of suburban development into quaint towns and villages and the concretization that accompanies it, the increasing proximity of retail outlet shopping into greenbelt stretches of bucolic landscape and the expansion of road and highway networks. Yet none of these changes threaten the fundamental nature of the British landscape only a few miles further away and much of this landscape has remained unchanged for decades. The general pace of decline is slow, an almost imperceptible ratcheting down from pristine old growth forests to managed modern landscapes taking place over centuries.

But what about ecosystems that have changed much more recently, under our noses, within the last few generations?

Some of the world’s most rapidly changing ecosystems are in the marine realm. Historically, we have viewed these ecosystems as vast and inexhaustible, mysterious and immense. We have fished, dredged, long-lined, blasted, and purse-seined the oceans, from the surface to the sea floor, with increasing intensity, especially over the last 50 years. Only their vastness has saved them so far. And yet, like mighty sepulchers, they too are approaching their ecological end points.

The change in these ecosystems has occurred within the professional lifetimes of the scientists who have studied them. In the last 40 years, most global fisheries have crashed, large consumer species have become rare, and underwater habitats such as coral reefs have vanished. These changes have occurred so quickly that the baselines of “what is natural” in these systems are radically different for the seasoned scientists in their 60s and the newly-trained scientists in their 20s. The result is an emerging community of marine scientists who did not witness the declines, have no personal connection to the losses and who fell in love with the oceans when they were already just shadows of their majestic former states. This shifted baseline constrains the ability of conservationists to imagine possible goals and objectives for ocean ecosystems that are outside the scope of their immediate experience, but which might nevertheless still be attainable.

The recent and rapid decline of the oceans means that the problem of shifting baselines, while it exists as a barrier to conservation globally, is particularly acute in marine conservation. If the current state of Planet Ocean no longer resembles its natural state, with some of its capstone ecosystems like coral reefs now existing in zombie form – neither truly alive nor truly dead – then the triage biologists who study them are in fact necrophiliacs, in love with the dead (or nearly dead), the moribund, the walking wounded.

In the face of such declines, and in spite of our psychological obstacles to imagine a future that is richer than the one we inherited, how should we respond? An unfortunate consequence of the rapid decline of these ecosystems is a tendency to focus on the rate and seeming inevitability of decay. But what would happen if we instead shifted our focus toward the wondrous, toward the life forms which are most resilient, those which persevere despite the ever-longer list of threats and the death by a thousand cuts to which they are all being subjected? It is the life within these nearly dead ecosystems that fascinates those of us working in the realm of marine conservation. For this reason we must cling to the signs of vitality and regeneration that still remain, to the myriad ways that life maintains itself.

Hope is a human commodity that is both precious and yet possessed in infinite abundance. The poet Emily Dickinson called it “the thing with feathers – / that perches in the soul.” As long as hope remains perched in our souls, we still have a chance to influence our environmental future. But lose hope, and we lose our potential for action. As we study and appreciate what has been lost, we must also treasure the fact that life itself has the ability to mystify and inspire. For in research, as all things, the loss of hope is an evolutionary dead end.