Good Sex: An Interview with Sharon Gannon

By Anna Louie Sussman

Sharon Gannon, the co-founder of the popular Jivamukti Yoga school in New York, author and outspoken vegan has long taught that veganism, as part of a lifestyle dedicated to avoiding the harming of all living beings, leads to spiritual enlightenment. Like the barefoot priests of Latin America’s liberation theology movements, Sharon Gannon’s philosophy links spiritual oppression with one’s material condition. It’s not just healthy and good for the environment, she explains, but the first step on the road to world peace.

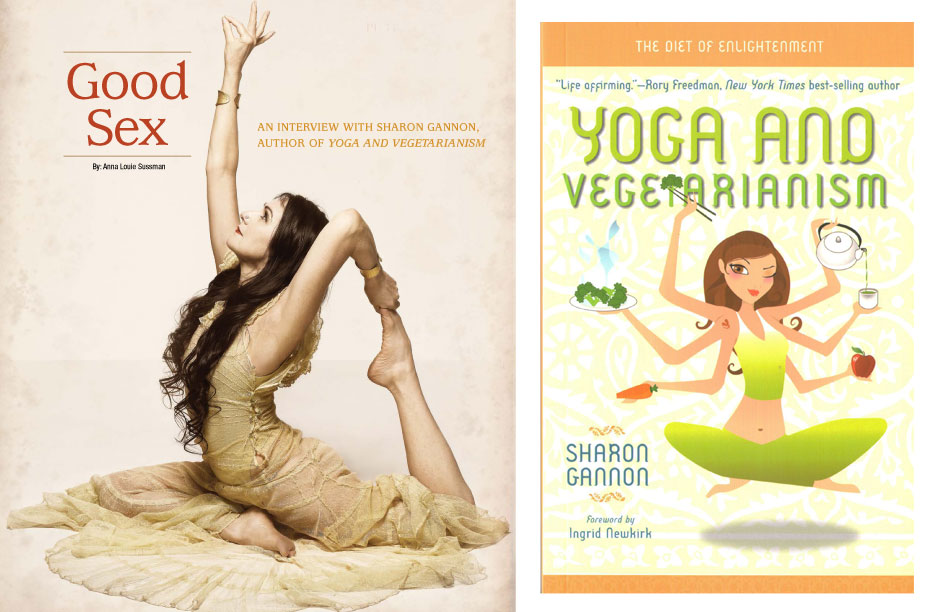

In her book Yoga and Vegetarianism, Gannon grounds the vegan lifestyle in yogic principles. She elaborates on the relationship between the five yamas, or directives, of the guru Patanjali’s yogic philosophy, and the practice of veganism.

“Yoga teaches that our prejudices against others pose the biggest obstacles to our enlightenment and that any spiritual practice we undertake must help us to overcome these prejudices,” Gannon said. “So Patanjali gives these five directives (called yamas) to help us overcome prejudices towards others,” including what Gannon calls “speciesism,” or the view that humans are separate from and superior to other living creatures.

It gets rather personal in the chapter called “Good Sex,” in which she unveils the abusive sexual practices involved with raising animals for consumption.

“The sexual abuse of animals is ingrained in our culture, and it expresses itself in the practice of breeding, genetic manipulation, castration, artificial insemination, forced pregnancy, routine rape and child abuse, which all fall under the category of ‘animal husbandry,'” she writes.

In one passage, she walks the reader through the life cycle of a dairy cow, from its days spent in a tiny stall to her continually forced insemination by syringe to ensure a steady flow of milk and ultimately to the slaughterhouse. Easy reading it is not.

Gannon generously shared further insights into the relationship between veganism and good sex in a written interview with Red Flag.

An Interview with Sharon Gannon Author of Yoga and Vegetarianism: The Diet of Enlightenment

Anna Louie Sussman: You observe that the consumption and instrumentalization of animals parallels how men sometimes treat women. Can you please explain why you decided to call chapter 5 “Good Sex” and what you meant by that? For people who haven’t read the chapter, what are those parallels?

Sharon Gannon: I think “Good Sex” is not only a catchy title but it aptly describes what brahmacharya actually means. Brahmacharya does not translate literally as celibacy. Brahma is the name of the Hindu god of creation and charya refers to a vehicle—we get our English words car and chariot from the Sanskrit word charya. Sex is potent. It is perhaps the most creatively potent experience we can engage in, as it can result in actually creating/manifesting a new being.

It also sheds light on what is perhaps the most hidden of all the cruel perversities associated with raising animals for food—horrid sexual abuse—the opposite of good sex.

Most people don’t see animals, certainly farm animals who are raised to be slaughtered and eaten, as having a sexual life. Somehow in their denial they think that animals just kind of grow like apples on a tree and are there for the pickin’.

The truth is that all animals raised for food are sexually abused at the hands of farm and slaughterhouse workers—and we are talking about billions of beings every day all day all over the world. This sexual abuse is so prevalent and so common that it is regarded as business as usual. The phrase “animal husbandry,” which is used by the agriculture and farm industries, pretty much says it as it is. It is at the same time a dirty secret and an openly acceptable practice. Adult animals are routinely masturbated, raped, and artificially inseminated in farms and factory farms. Tethered baby “veal” calves, desperate to suck, are sexually taken advantage of by farm workers and many animals in slaughterhouses are also raped by slaughterhouse workers for “fun” before being killed and dismembered.

ALS: When did you first become aware of these linkages between the way humans treat animals and the hierarchical relationship between the sexes? Why do you think so few people make that connection?

SG: Many human beings treat animals as if they were inanimate objects devoid of feelings, intelligence, consciousness or souls. I don’t see an animal as an “it.” I see other animals as people—male and female persons, each a distinct individual with feelings, thoughts, memories and ambitions. We should not forget that we (human beings) are animals too, and all animals are not the same, there are differences. I see human beings as different from other animals in the same way that I see a cat as different from an elephant and an elephant as certainly different from a bluebird. The differences are mainly in outer form; inside in our minds, hearts and souls we are much the same.

Why don’t more people make the connection? Animals can be bought and sold. It wasn’t that long ago when we bought and sold other human beings, and it wasn’t that long ago when a man owned his wife (or wives) and his children. With ownership comes the privilege to do whatever you want with the thing you own—it is your property. I think that basically it comes down to low self-esteem. Those who crave power over others lack self-esteem. Misogyny and Speciesism—they seem to go hand in hand, who knows which came first? They are both the outcome of low self-esteem.

My theory is that sometime in our distant past we did not live in patriarchical societies where men dominated women like today. There may have been a time when women were regarded as special beings because they could magically manifest a new being—give birth to a child. Perhaps at that time the connection between sex and procreation was not understood. When animals were confined it became apparent how sex led to pregnancy. People started to breed animals and this, I suspect, is when the magical, “special” quality that was reserved for women wore off.

ALS: Do women and men respond differently to these ideas? If so, what sorts of responses do you get?

SG: I have found that just because women are female doesn’t mean they aren’t misogynistic. The cultural indoctrination goes deep. Many women when they wake up and realize the misogyny, which underlies our culture, react with anger towards men. In a similar way many people when they wake up to the realities of animal abuse react with anger towards all non-vegans and definitely against the animal user industries. The interesting thing is that most of the men who have an interest in yoga are also open to embracing both feminism and veganism—perhaps these men are ready for a course of radical deprogramming. With the yoga practices one is not so seduced by anger and blame.

In my experience when the truth is revealed about animal abuse, both men and women react first with disgust, followed by horror, incredulousness, sadness, guilt and shame, and some close down after feeling powerless and not wanting to see, hear or know anything more. Some take a next step and respond with anger, at the slaughterhouse workers, or the corporate multi-nationals who profit from animal abuse, or their parents for eating meat, or meat eaters in general. Those who stay and are willing to follow their feelings to the next level usually are able to let go of the anger enough to feel empathy towards the animals who are being abused, and if they stay with this exploration longer the empathy gives way to compassion. It is at this point that real progress can be made towards putting an end to speciesism.

I remember after the courageous book Dominion came out, I was so intrigued that such an articulate, pro-animal rights book could have been written by not only a conservative Republican, but by the senior speech writer for President George W. Bush, that I was determined to meet this man. I contacted him and then traveled to Washington, D.C. to see him. He invited me to the White House to meet the president, which I declined saying that I was more interested in meeting him and that that was the reason for my visit. He appeared flattered and very graciously invited me to his modest home in Arlington. The first thing that he said to me while we were sitting together in his living room was, “I am very surprised that you, a yoga teacher, would be interested in animal rights and have read a book like mine!” To which I replied, “Me? what about you, Mr. Speechwriter?” So from the get-go we connected quite well and became friends.

ALS: There’s immediacy to how you tell the story of the cow’s life. Can you tell me about researching and writing it?

SG: In Chapter 5 of the book, I tell the life story of a typical dairy cow in order to give the reader the opportunity to make a connection to what actually happens to a dairy cow and thereby tap into the reader’s innate empathy. I feel it was painful but also necessary to write it in the way I did. We human beings are a bit strange in many ways, one of which is that when we hear about one animal being abused we feel outraged, but when we hear about billions of animals being abused we tend to tune out and feel powerless. I wanted to encourage people and help them see that they aren’t powerless. I wanted them to see milk as far from the benign food that we have been conditioned to see it as. I wanted to expose the truth of the misogyny and speiciesism involved in the dairy industry—that a female is kept as a slave—a sex slave—confined, raped, abused and degraded because she is a female and can be exploited for being a female—she can be forced to produce milk and birth babies.

Also I used the story of a cow because I wanted to make an impact in the yoga world. I knew that many of my readers would be vegetarians, but they drink milk and consume other dairy products because they feel that this is in accordance with a yogic lifestyle. They ignorantly think that this involves no harm to cows and that by consuming dairy products they are still following the dictates of ahimsa (non-harming) as described in the yoga sutras. Many people have said to me after reading the book that it was chapter 5 which did it—made them go vegan. Okay, so mission accomplished, good.