Featured Artist : Walton Ford

There is a Vietnamese allegory that tells the story of how tigers earned their stripes. The story begins with a golden tiger who witnesses the baffling sight of a man, whom he sees as inferior by comparison, forcing a water buffalo to toil in the rice paddies each day at his command. The tiger seeks an answer from the buffalo, “Please tell me, what is the secret of his magic power?”

The buffalo calls this power trí thông minh or “intelligence”. The tiger becomes mystified by this mysterious power and appears next before the farmer asking if he can show him “this thing called intelligence”. “Unfortunately,” replied the farmer, trying to hide his terror, “I left my wisdom at home today, but if you would like I can go and fetch it for you.” The farmer only agrees to return with his intelligence if he can tie the tiger to a tree. He convinces the tiger it is only to ease his fear that he might lose control to his own hunger and eat his water buffalo. The tiger is so smitten with the idea of obtaining the power of “intelligence” that he agrees.

The farmer finally returned with a bail of straw in each hand. He stood before the rope-bound tiger and laid the straw at his feet. Confounded the tiger looked on as the farmer lit the straw. “Behold my intelligence!”, he shouted, as flames quickly encircled the tiger and burned him fiercely.

The fire soon burned through the ropes and the tiger leapt in a fury of pain and anguish from his fiery prison back into the jungle from which he came. The searing ropes still encircled his golden fur – setting it’s tone to a deep amber hue and leaving black markings where the burning ropes singed and scarred his body forever.

Walton Ford’s paintings too can be read like allegories. What you see on the surface is just one intricate and alluring layer of a story that eventually enfolds all of us into its meaning.

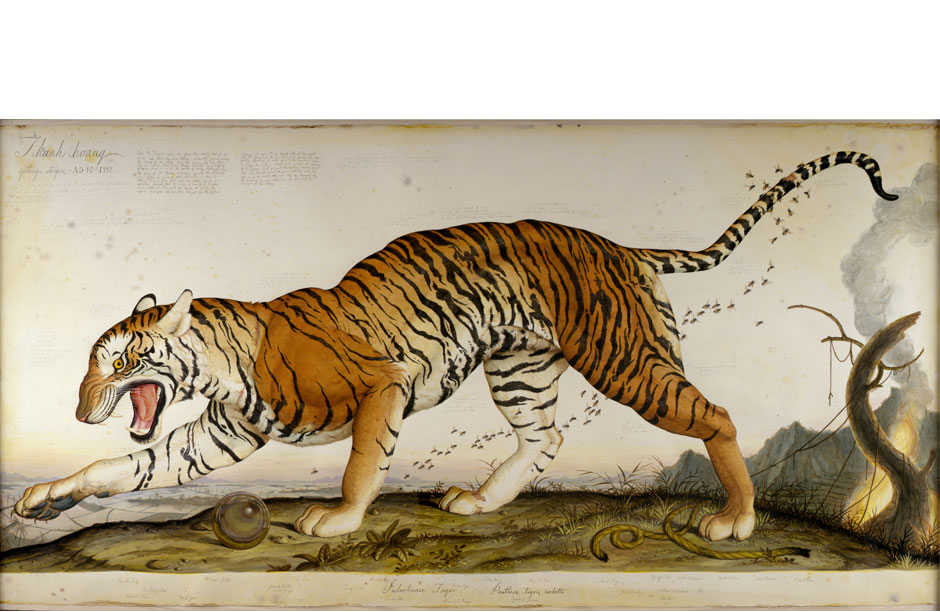

Ford’s painting Thanh Hoang (1997) seems to tell the same story as Trí Thông Minh (2013), depicting an angry tigress with the same singed ropes at her feet. The subtitle scripted in delicate pencil directly on the painting even reads “getting stripes AD 40-1997”, but the dates refer to another “tigress” – the nation of Vietnam whose documented history is one of the longest in the history of human civilization. Scrawled on the bottom of the painting under the feet of the tiger in the same faint penciled in script are the names of all the people who stand upon the major milestones of that long history, like John F. Kennedy, Ho Chi Minh, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon. It begins, though, with the Tru’ng Sisters. Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị were the first to successfully rebel against Chinese rule. In 40 AD Trưng Trắc led them to independence and became their queen, but by 43 AD the Han Dynasty struck back sending in an army too powerful for the Tru’ng sisters to stave off. They committed suicide to avoid being captured and Vietnam returned again under Chinese rule.

“All of my paintings of animals are activated by a human presence,” Ford has explained. By interweaving the traits of human emotion and drama into his portraits of animals Ford is able to lift for a moment the veil that has been set between “us” and “them” – between humans and animals. The story of how the tiger got its stripes is a perfect allegory for this illusion. We believe it is intelligence that sets humans apart from animals, but in truth an intelligence so easily guided by fear and greed which can be used to bind, separate and singe what is beautiful, strong and majestic is more like a weapon of destruction than a trait to take pride in.