Ebb and Flow: Environmental Conservation off Cuban Shores

By Fernando Bretos

I stand on the Havana malecón — this bustling city’s majestic seawall only 90 miles from Key West. Ironically, it was built by the Army Corps of Engineers during the 1898 American occupation of Cuba. I look north toward “La Yuma,” the quirky name Cubans call the United States. In my 15 years working in Cuba, no one can fully explain the name’s origin. For some Cubans, Yuma means the lurking Yankee imperialist, while for others it is a place worth risking one’s life to get to.

I strain my eyes scanning the northern horizon. I try my hardest, but even on a clear tropical night I can’t make out the bright lights of America’s southernmost outpost of Key West. But I know it’s there. I know it’s close. My flight from Miami was in the air for all of 35 minutes.

As a biologist with The Ocean Foundation based at the Miami Science Museum, I have spent almost half of my 38 years studying the close biological links between Cuba and the United States and the rich marine habitats along Cuba’s 3,000 miles of coastline. The links are numerous; not only do almost two million Cubans live in the US, but our cultures and histories are intricately woven.

Cuba and the US have been associated long before there were people around to notice. Sea turtles, manatees, and the tiniest suspended offspring of fish and lobster have flowed back and forth well before Miami or Havana were large enough to light the evening sky. Later on, Hernando de Soto explored Florida and the southeastern US from a base in Havana in 1527. Pedro Menendez de Avilés, the conquistador and governor of Cuba, discovered the site of Miami and later actually founded St. Augustine, America’s oldest city. He was also operating from Havana.

My own family has been a part of these transmigrations. In 1895, during the Cuban War of Independence, my great-great grandmother went into exile in Tampa. My parents followed three generations later as “Pedro Pan” migrants: teenagers who left their families behind in Cuba at the height of the Cuban Revolution. Their thinking was that they would reunite in a matter of months. My mother has never returned to the island.

As a conservationist, the link that interests me most is biological. Florida and Cuba are joined by a narrow yet fast moving body of water called the Gulf Stream. This conveyor belt of biological and human passage has one stubborn feature: It only flows north. As a result, one country benefits more than the other.

All of the seawater departing the western Caribbean for the Gulf of Mexico passes south of the Florida Keys via the Florida Straits. Fish and lobster larvae, coral spawn, migrating sea turtles, and sharks hitch a free ride on this ocean freeway. This is the same body of water that hundreds of thousands of Cuban rafters have crossed to reach La Yuma.

This body of water is not the only thing separating our countries, which haven’t gotten along for almost six decades in part due to the embargo that has sought to overthrow the Cuban government with no success. As a result of academic restrictions, Cuba is a black hole in terms of our scientific comprehension of its biological riches. Over 50% of Cuba’s plants are endemic, meaning that they only grow in Cuba. The island is home to four massive coral reef chains that if lined up would be three times larger than the lush Mesoamerican Barrier Reef that stretches from Mexico to Honduras. Three of four of these Cuban reefs are almost as large as the Florida Keys. Cuban forests and plains host swaths of migrating birds making the rounds between their winter and summer homes. Cuba is home to amazing creatures, like the smallest hummingbird and the tiniest frog. Or the secretive almiqui, an ant-eating shrew that seem more likely to be found in Australia or Africa.

In 1999, I set out to prove that the Gulf Stream’s constant flow could move small marine organisms from Cuban waters to American shores. I wanted to dramatize that – no matter the political posturing on both sides of the Straits – protecting Cuba’s marine resources was critical to ensuring the health of our own reefs and fisheries all the way up to Massachusetts and as far west as Texas. I got a chance to work on an oceanographic research vessel out of Texas A&M University that received permission to sail from Cancun into Cuban waters to study oceanic currents. I hitched a ride on that vessel eager to prove a point.

My plan was to release 1,900 bottles off the southern coast of Cuba, each with a conspicuous yellow note inside. The nutrient rich and shallow, sunlit waters of the southern Cuba platform form one of the most highly productive marine areas in the Caribbean. On each piece of bright-yellow paper, the finder was asked to provide the date and the place where the bottle was found. Coral and fish larvae only live so long and in order to move passively over hundreds of miles, they would have had to get there quickly or succumb to the high seas.

My study was a crapshoot with little upside and plenty of drawbacks. For one, here was a self-proclaimed environmentalist and defender of the oceans essentially dumping glass into the ocean. I was sure to hear about this later.

We released our bottles off the coast of Cuba’s Isle of Youth and I returned to Washington, D.C., to wait. A few letters with yellow notes arrived in my mailbox and I eagerly opened them all. Most came from the Cayman Islands. But one day, precisely 46 days after our launch, a letter arrived from West Palm Beach, Florida. A week later, another bottle was reported from Port Aransas, Texas. I shouted with joy! If a vial had made the crossing to Florida in only six weeks, so could tiny fish or lobster larvae. And larger animals that swim would have it even easier.

This is critical to understanding the marine connectivity between our countries. Florida is home to 18 million residents and annually hosts upwards of 90 million tourists. Florida has seen unprecedented overuse of its coastal and reef habitats. The Everglades has been sucked dry and we spend billions of dollars importing sand onto our eroding beaches. We have taken too much out of the system and are relying on importing fish to feed the demand. Biologically, Florida and the US east coast are at the end of the supply chain. These areas rely on pristine habitats upstream more then ever. We depend on healthy Cuban marine habitats more than Cuba depends on ours.

Fortunately, our neighbor to the south has taken a progressive stance in terms of crafting environmental legislation and managing natural resources. Cuba also enjoys a low population density, hosts only three million tourists per year and practices small-scale organic agriculture out of necessity, all factors that have led the nation to be coined by a recent PBS Nature documentary an “accidental Eden.” Cuba has declared a goal of designating 25% of its land and water as protected areas by 2020, a goal that is halfway complete.

Not all the grass on the other side is green. Without help from the Soviet Union, Cuba turned to tourism in order to survive. While tourism figures are paltry compared to those in Florida, they are on the rise.

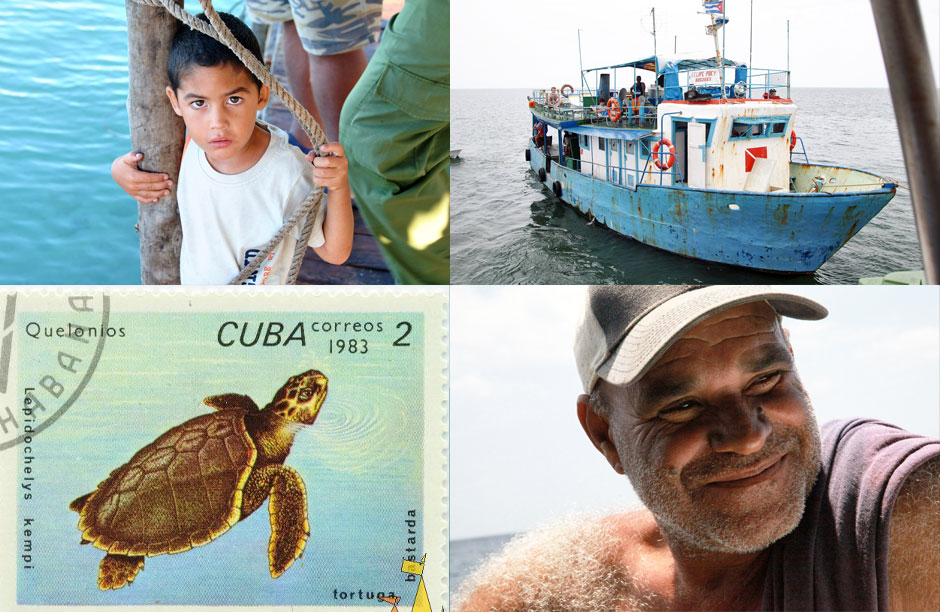

My experiment was by no means the first nor the last to demonstrate this phenomenon. Oceanographic studies have detected the movement of larvae and algae over broad stretches of the Florida Straits. In 2012, I got another chance to prove my point. In this case, instead of glass bottles, I decided to see if sea turtles born on Cuban beaches would make their way to the US. My Cuban colleagues from the University of Havana and I tagged the backs of five sea turtles nesting at Guanahacabibes National Park in August 2012.

Sea turtles are enigmatic creatures. They have been on the planet in an unchanged form for over 200 million years, making them quite highly evolved organisms. Out at sea for most of their lives, we know very little about them except that female turtles return to land to lay their eggs on the same sandy beaches. This roughly annual homecoming provides a unique opportunity to peer into their curious life histories. However, wherever they migrate, we know that sea turtles display what is called philopatry, meaning that a turtle hatched from one beach will return to that same area to nest. So while we couldn’t expect our Cuban turtles to nest on American beaches, we could learn quite a bit about where these turtles go to feed or mate.

I have worked on the Guanahacabibes Peninsula since 2001, studying a significant population of green sea turtles. It is a wild place, home to dense forests and beautiful coral reefs. The conditions are difficult, but we affixed our tags on our indifferent hosts’ carapaces and waited for a response. Initially, two of the five turtles beelined straight for Florida. I watched their tracks every morning from my office computer. Were they traveling to Florida to feed on seagrass beds in Miami’s Biscayne Bay? Ultimately, Harriet and Conchita made a U-turn to the south halfway from Florida. The good news is they found ample feeding grounds on seagrass beds in southern Cuba, Mexico, and Nicaragua.

Cuba and Florida are among the most important sea turtle nesting areas in the northern Atlantic. My study solely proved that turtles and other marine life do what they need to survive a tough life at sea. In a conservation context, it also showed that we have more work to do to develop cross-boundary policies to protect shared resources such as sea turtles. But how can we create effective policies to ensure the protection of migratory species when two countries don’t talk to each other?

We need to take a step further in engaging with one of our closest neighbors, especially with so much at stake. With an increase in tourism to Cuba comes an increased pressure on Cuba’s fisheries and coral reefs. The status quo of international relations relegates the US to the sidelines. By working with the conservation community in Cuba, my hope is that building bridges between our countries will ensure that Cuba avoids our mistakes, and that both countries formulate conservation decisions that effect species shared on both sides of the Florida Straits. Though more work needs to be done to understand what is at stake, marine science provides one of the few avenues for legitimate cooperation with Cuba. And as I stand on the Havana malecón, I still can’t make out Florida’s lights, though I know we are connected by something more important.