Bloodlines

By Yasmin Newman

When James Harrison was just 14 years old he underwent major chest surgery. As a result of severe blood loss, his life sat on the line, dependent on the redelivery of blood. He was given 13 units – a significant transfusion; he made a full recovery.

Young James was changed forever. A country lad from Junee, a small town in the Australian state of New South Wales, he’d been raised with wholesome values and good stock for role models, including his dad who was a blood donor from way back. After the operation James made a pact to donate blood once he turned 18, the then-legal age for donations. “Good,” his father simply replied.

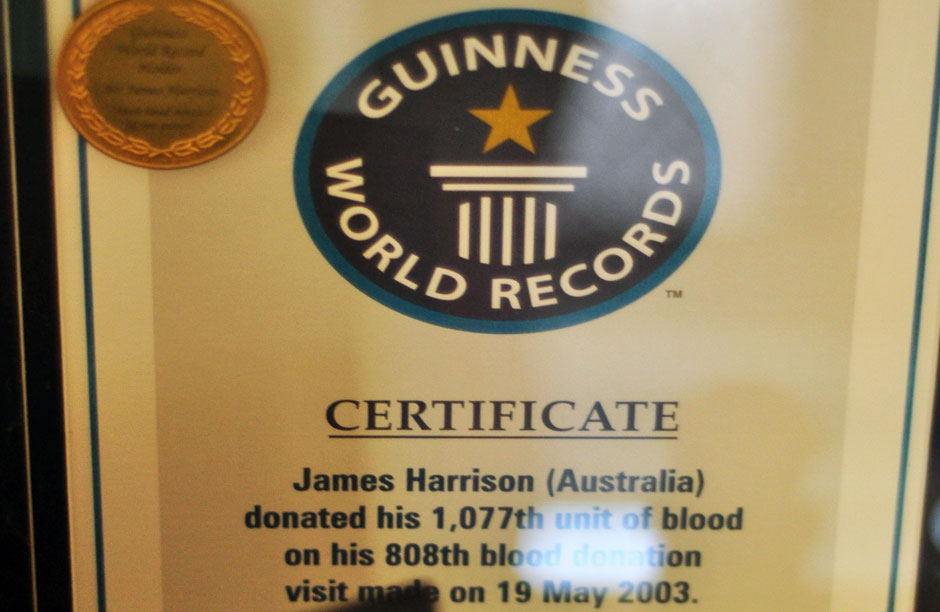

True to his word, James began donating following his 18th birthday and has continued with religious constancy for the past 56 years. Every one to two weeks he takes the train to Sydney to donate at the principal blood center in the CBD. If he happens to be traveling he drops by the local or mobile blood bank. James once held The Guinness Book of Records for the highest number of blood donations. Today, at 1,003, he is the Australian record holder.

On the day of our interview it is the seventh anniversary of his wife Barbara’s passing. She was also a blood donor. He recounts “synchronizing donations” and enjoying their trips to the city and the coffee they’d share after.

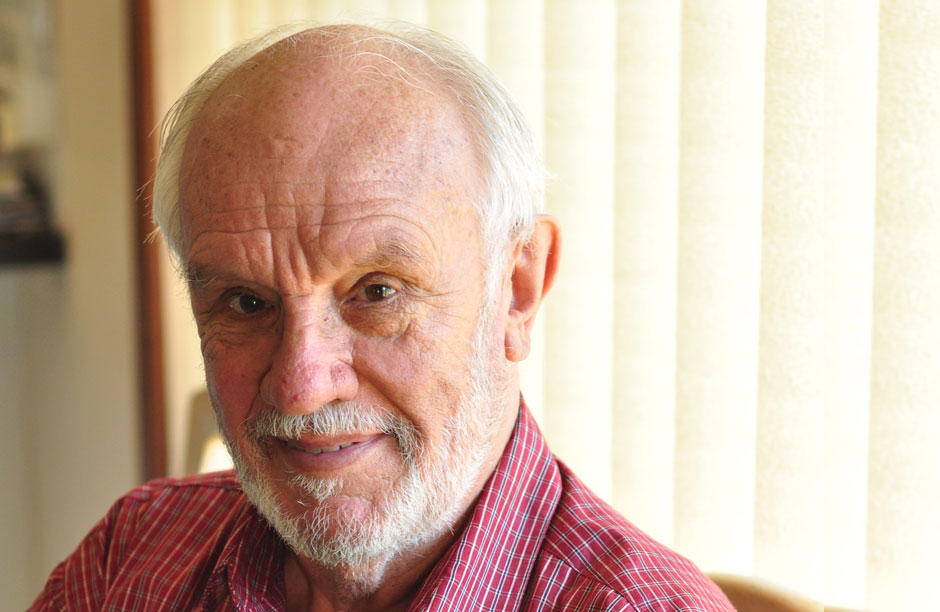

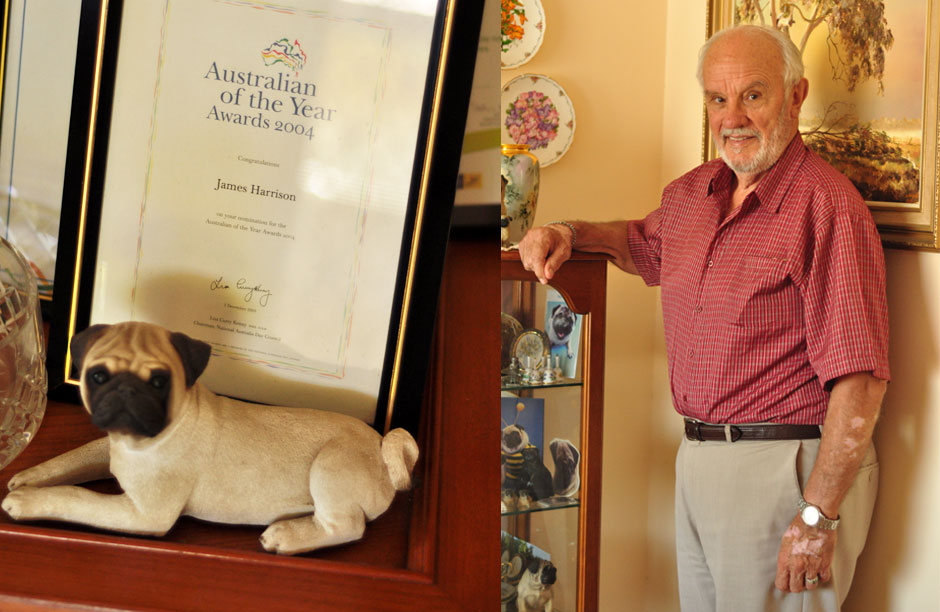

Sitting is his living room the 74-year-old is dressed in well-ironed pants and a smart short-sleeved button-up shirt, similar to the ones my grandpa used to wear; he was of the same generation. His house is filled with trinkets, collectables and tokens of appreciation. There are dozens of dog figurines decorating the room, all Pugs – he and his wife were hobbyist breeders for over 40 years. On the shelves are well-kept folders filled with a curated stamp collection and plaques from his incumbency as seven-year-president of the local Caravan Club. There is also a wall covered with some of the country’s most prestigious awards, including the Order of Australia (OAM) for his work with blood. It takes pride of place in the entryway to James’ beach-town home, but I suspect its placement is not one of preference, but one of respect. James is at heart a community serviceman, irrespective of the accolades.

I am touched by this gentleman’s humility and uncomplicated outlook. Giving blood is something he does because he can. For Australians, donating is as simple as deciding to, but only three in 100 make that step. Why is the rate so low? One donation can save up to three lives. As James points out, one of these can be your own. He recalls meeting countless scared first-time donors. “If they faint, it’s mainly because they’ve built it up so much in their head!” – he speaks with empathy. It’s a painless procedure, but an individual’s ability to donate can also be effected by their veins. It’s something James understands from experience. He shows me his two arms: from his right, now marked by scar tissue, he’s given 993 times; from his left, only 8. “It doesn’t hurt like stubbing a toe,” he replies to my question of pain. “I can just feel it.”

The long-time donor describes the changing landscape of blood donation since he began. He points to increasingly busy lives, particularly of city dwellers, who struggle to get time off to work when donation centers are open, as well as turbulent economic times. The Australian Red Cross Blood Service receives Class Three Hospital funding, but tighter governmental budgets have meant fewer resources across the board. In the past, ongoing donors’ efforts were celebrated with ceremonies upon 100, 200, 300, etc donations. These simple gatherings have been scaled back. Even James’ milestone one-thousandth was held in the center’s foyer instead of an actual room.

Don’t let this paint a bleak picture: technological advancements have made for easier blood extraction and the immaculate permanent and mobile centers are testament to the Blood Service’s well-run offering. It’s about getting people in the door and rolling up their sleeves. James agrees: “I don’t think they donate ’cause of what they get out of it,” he says in reference to awards. “They donate because they know what they’re leaving behind is necessary to keep people alive. We’re not in it for money, because there’s no money in it.”

Giving blood is entwined in the bigger story of organ donation, which can be a contentious issue involving questions of religion and medical procedure. James and I are in the same pro-donation boat; organs aside, blood is less complicated. Blood can be donated every three months and plasma every week; in the interim, the body self-rejuvenates what’s been taken. If you’re sick, you’re simply not eligible.

In James’s case, his benevolent actions were heightened by a fateful twist on his path of blood donation. In 1966, doctors discovered a rare antibody in James’s plasma that prevents newborns from dying of Rheus disease, a severe form of anemia. The condition stems from a difference in blood type between a mother and her unborn child. For James, the antibody was not naturally present until he was mistakenly given Rh-positive blood instead of Rh-negative during that life-saving transfusion he had at age 14. The result, benign for James, would be miraculous for countless mothers and children, who have been administered the Anti-D vaccine derived from James’s blood. “They keep telling me that I’ve saved 2.4 million babies,” he says. “How they know, I don’t know.”

Later, after childbearing age, James’s wife opted to be injected with the antibody so she could donate Anti-D blood too.

I ask if his wife’s passing has been made any easier by the knowledge of the lives they’ve jointly saved. No, but his daughter was injected with the vaccine for the birth of her second son; this has had a profound effect. “It made me realize even more how important the Anti-D vaccine is.” James believes there are now only 50 donors in Australia. “When Barbara passed, they lost one,” he says sadly.

James himself has just begun donating again after a nine-month break to have an overactive thyroid removed. “The only way to continue to donate was to have it irradiated,” says James, who later revealed that he could have taken medication for the condition, which is markedly less invasive.

“Do you feel like a hero?” I ask James. “No. Heroes goes to war,” he replies.

In my opinion, heroes are selfless. And come in a range of blood types.