“Manuscripts Don’t Burn”

By Nathaniel Sandler

Books themselves are a fairly bad investment. A standard trade paperback effectively depreciates down to $0.00 as soon as it leaves the store and is typically used only once. There are very few other investment opportunities that are as fiscally unforgiving. With this realization comes another, that what we are actually purchasing is the solace of the object and the comfort of its story. Readers surround themselves with texts they have read – or think they will read. I myself sleep amongst a rolling fort of books – my walls cobbled unevenly with spines of bound paper. I find some unknown consolation in their presence.

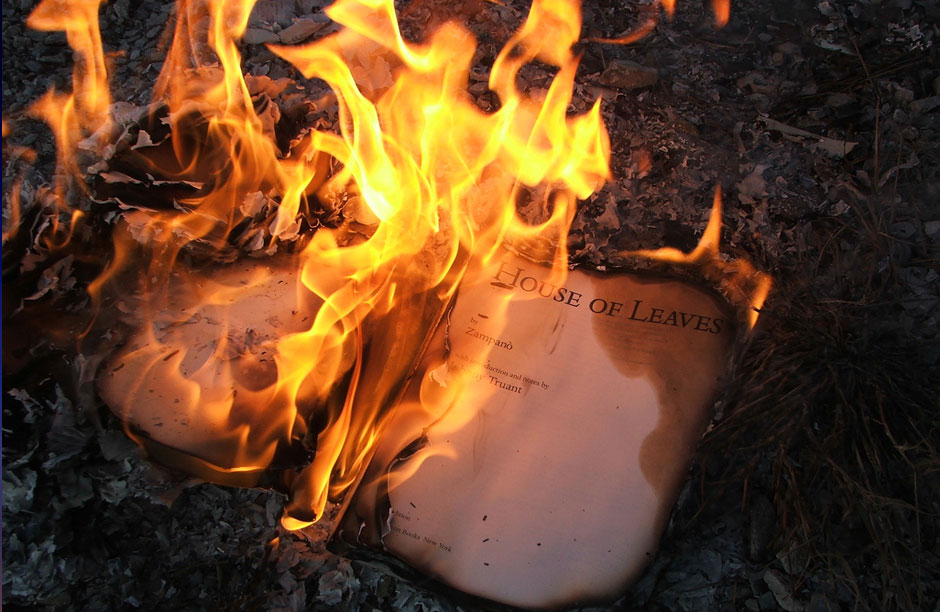

The power of books is never more apparent than when they inspire the act of biblioclasm, or the destruction of books. Book burnings are bonfires of ignited passion, but the burner is typically against the words contained within the pages – the ideas – not the object itself.

One of the lesser known incidents of book burning took place in tenth century Muslim Spain where the work of poet and polymath Ibn Hazm fell victim to biblioclasm due to persecution for his openness to the beliefs of other religions. His most famous work The Dove’s Necklace is best known for its sensuous poems of amorousness. He produced around 400 works in his lifetime covering a great many other topics such as Law and Medicine, though only around 40 still exist. This is due primarily to the confused fervor of the King of Seville at the time, Muhammad Ibn Abbad al-Mutamid, sometimes known to his people as the protector of poets. He was a poet, married to a poet, and fathered poets, which makes his decision to have all of Ibn Hazm’s works destroyed particularly curious. One would hope that the leader of the realm would support poetry since he professed to be its protector.

Even more perplexing is that after al-Mutamid was ousted as King and sent into political exile, he spent his time writing poetry passionately emulating Ibn Hazm, the man he personally humiliated and whose writings he persecuted. One can almost envision al-Mutamid wandering penniless throughout the gardens of Morocco, where he was exiled, filled with regret. We can only draw assumptions from history, but it seems obvious that al-Mutamid was terrified of the gift of Ibn Hazm’s words.

With the advent of digital books, a new form of biblioclasm is in our midst. That the book may not live too far into this millennia is sobering. As of the end of last year eBooks actually outsold paper books on Amazon, the worlds largest online book retailer. Purists, and I can be accused of being one myself, find the idea abhorrent. There are plenty of arguments in favor of the end to the book as an object. Consider, for instance, in 2007 it was estimated that around 3 billion books were sold each year which turns out to be around 400,000 trees. That is a lot of stuff and a lot of trees. Yet, we are still drawn to the experience of a book in our hands.

Reading a book is a private action. Alone the reader dives into whatever world provided by the author and illuminated in their own imagination. Some stories stay with a person for a lifetime, and some are flushed away immediately. This relationship with stories transfers to the objects themselves and thus some books, rare or sentimental, are kept for the duration of the owner’s lifetime. Some collect obsessively regardless of value, and some don’t care for the book at all once they have finished reading it. One’s relationship with books is personal, like the stories.

In his famous essay “Unpacking My Library”, Walter Benjamin explores books as objects in relation to a collector and various ways one obtains the objects. At one point Benjamin describes each book in his collection as a “chaos of memories”, or a compilation of moments during the life of the collector linking each book to its acquirement. The owner of the book inadvertently creates a loose personal timeline of biography seen through the act of surrounding themselves with objects, lining the walls of their home with various pinpointed moments of their lifetime.

Can you remember the moments you bought each of your books? Looking upon my own bookshelf I can take myself to certain places, to the bookstore in Starnberg Germany where I bought a first British edition of The Town by Faulkner – to that moment in my travels. It’s possible that the internet has dulled the phenomenon of actually purchasing a book in a specific place, but I could also mention my copy of Samuel Johnson’s 18th century The Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (Volume One) purchased at a time in my early 20s when I would check into eBay daily searching for “antiquarian books” at a bargain. Or perhaps most tellingly is the strangeness I feel when I see my copy of the unexpurgated Gargantua and Pantagruel from the 1950s by Rabelais that I stole from my high school library. It takes me back to a time when I thought fleecing a library of important tomes was a rite of passage.

I bring up these three books specifically because I haven’t actually read any of them. Why do I even keep them? I remember the moments when I got them, but I don’t know the stories. Even the gigantic and beautifully bound Gargantua and Pantagruel – I’ve had it for over ten years and I’ve only read select parts.

Getting rid of a book can be terrifying for a serious collector. It can never go in the garbage. Biblioclasm, comes in many shapes and forms, not just fascist bonfires of misplaced revolutionary hate. For any book-minded intellectual it’s an unacceptable sin. What many people don’t assume is that books are destroyed regularly behind the scenes when places that house them, create them, and distribute them do not know what to do with them. Publishing houses, libraries, and bookstores are all regularly faced with space issues and overstock. Unfortunately the simple fact of the matter is that pulping them or trashing them is simply cheaper than creating the resources required to donate them.

Little known Czech author Bohumil Hrabal penned one of the most masterfully underrated novellas of the 20th century entitled Too Loud a Solitude about a man who works in a paper crushing and disposal mill, yet he goes to great lengths to salvage each rare and banned book from destruction that passes through his watchful eye. The plot is loose and the story is mainly told stream of consciousness, but throughout, the main character, Hanta, desperately compiles heaps of manuscripts and tomes while building an outlandish lexicon of personal knowledge on a vast array of topics. Despite outwardly being somewhat of a simpleton, Hanta creates a link between compiling actual objects and saving them from destruction with the expansion of his own intelligence. It is no secret that a great deal of people correlate their book collections with their level of erudition. Hanta is a tragic figure. His intellectual aspirations and his actual intelligence do not match up. Sometimes linking objects with intelligence is a smoky mirror.

What then if we begin to move away from the book as an object? I am not going to bemoan the death of the book. I think that we will continue to covet stories and the ideas that hatch within them and ourselves. Perhaps you will not remember the time you bought a novel or poem collection, but the changing nature of the printed word will never be able to take away the setting and emotion evoked when you read it. As the famous Russian novelist Mikhail Bulgakov once said “Manuscripts don’t burn.” Bulgakov found this out the hard way after having to re-write his masterpiece Master and Margarita after the original manuscript was lost in a fire. But the story was still there, waiting and lurking. Perhaps owning a Kindle will change the way stories and how the knowledge garnered from them is reflected in the object’s owner, but what will never die is the need to relate to stories.