Buddhist Economics

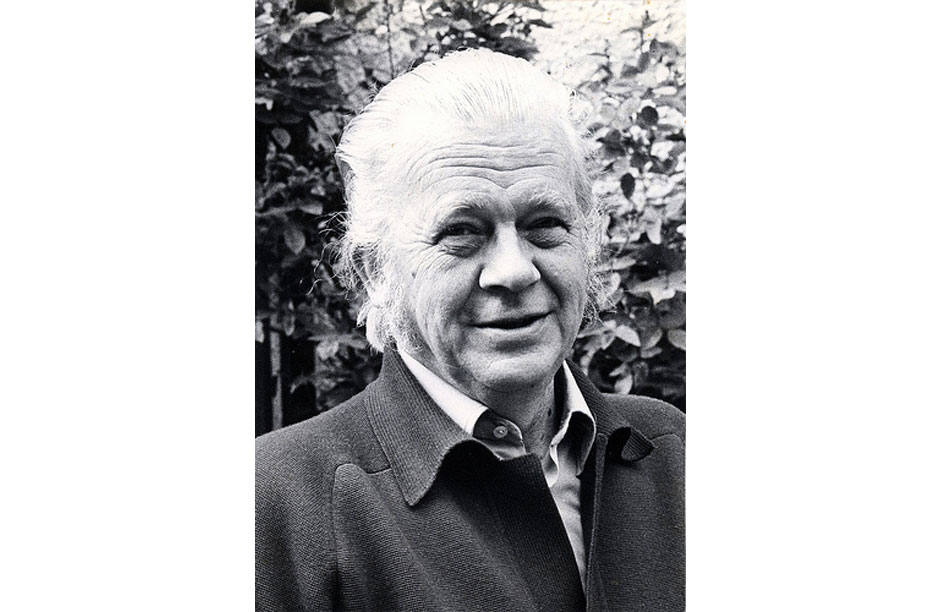

In 1973 a little book came out with a very large message: Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered. Its author was not a hippie or a yogi from the East, but rather he was outwardly what one might categorize as a “square”. His name was E.F Schumacher and he was a German-born economist who served as an Economic Adviser to the British government for over two decades. At the time he published Small is Beautiful Schumacher was 63 years old. Only 4 years later he would pass away of a sudden heart attack leaving behind “Small is Beautiful” as his veritable last words.

In 1955, during his post in the UK, Schumacher was sent to Burma as an economic consultant. During his time there he discovered that modern Western economics – the school from which he came – valued products over people.

He wrote: “From a Buddhist point of view this is standing the truth on its head by considering goods as more important than people and consumption as more important than creative activity. It means shifting the emphasis from the worker to the product of work, that is, from the human to the subhuman, a surrender to the forces of evil.”

When he returned he drew up an essay which he titled “Buddhist Economics” and handed it to his colleagues in the economic division of the British government. The response was: “Mr. Schumacher, economics is all very well, but what does Buddhism have to do with it?” To which he replied: “Economics without Buddhism (without spiritual, human, and ecological values), is like sex without love.”*

Within Small is Beautiful Schumacher’s ideas were expanded. He covers topics under chapters he titled: “Technology with a Human Face”, “Peace and Permanence”, “The Greatest Resource–Education” and “New Patterns of Ownership”. He set forth concepts that broke through the current modes of production like the term he coined “Natural Capital”. Schumacher identified that nature and all its bounty from fossil fuels to timber is improperly and dangerously categorized as income instead of capital. In basic terms we have come to see nature as an unlimited resource which is in fact limited and should be valued as such.

Small is Beautiful did not create an international stir when it was published. Its ideas weren’t even assimilated by the time the next decade rolled around. Instead – like the small roots that a seedling puts out to explore its new ground – Small is Beautiful took its time to seep in and take root.

The environmentalist and social activist Paul Hawken, wrote an introductory essay for the 25th anniversary edition of Small is Beautiful, which we have published below with his permission. Hawken published a book on Earth Day in 2007 titled Blessed Unrest chronicling and compiling a giant movement made up of many tiny parts. The “movement” is the global movement towards change, which was not started by governments or corporations, but rather by concerned mothers, grassroots nonprofit groups, school students sparked by their passion, corporate employees seeking a meaningful outlet from their daily grind, and baby boomers hoping to create a better world for their grandchildren – it is a movement born from the same principals that Schumacher identified in Small is Beautiful 35 years earlier. Both Hawken and Schumacher were prescient enough to see that change is imminent.

In the words of Paul Hawken – an excerpt from his introduction to “Small is Beautiful: Economics As if People Mattered” (25th Anniversary Edition).

I met Schumacher twice, and heard him speak to different venues in England, New York, and California. In Palo Alto, California, he spoke to a diverse audience ranging from students, political activists, and environmentalists on one hand, and academic deans, economists and executives from high-tech companies on the other. He was able to establish a rapport across the spectrum of listeners for three reasons: his humility, his erudition, and his sense of humor. At the time, the inevitability of his ideas appeared overwhelming in the face of the failure of the Western government’ environmental, energy and social policies. But that was not to be the case. While myriad movements grew out of or were empowered by his work, the world as a whole has moved powerfully towards consolidation, gigantism and globalization.

Does this mean his ideas are invalid, outdated, or impractical?

…If we conclude that good ideas are only those taken up by mainstream society, then Small is Beautiful is an outdated shibboleth. But there is another possibility–that Schumacher articulated truths that are fundamentally true regardless of time, culture, or prevailing economic system. One of the important ideas, synonymous with the title, is that there is an optimal human scale, size, or relationship inherent in economic activity, a geometry of life that is independent of economic theory, even his own. Schumacher was not suggested a return to another age as he was sometimes accused. Rather in both his monastic retreats and in the rhythm of Burmese village life, he made an observation that was both heretical and edifying: There are inherent thresholds in the scale of human activity that, when surpassed, produce second-and third-order effects that subtract if not destroy the quality of all life.

Without question, the most exciting work today is not creating another business (there are over 100 million in the world), but what is called “social entrepreneurship,” the extraordinary act of bringing people together to transform the institutions that rule, harm, and overwhelm the nature of human existence and our relationship to living systems. There are today over 30,000 nongovernmental organizations in the United States and perhaps another 70,000 worldwide that are working towards one or more of the ideas presented within this book. The tens of thousands of organizations that are working towards a sustainable world are, on the whole, diverse, local, underfunded, and tenuous. Scattered across the globe, from Denmark to Chile to Kenya to Bozeman, Montana people and institutions are organizing to defend human life and the life of the planet. They address a broad array issues including environmental justice, ecological literacy, public policy, conservation, women’s rights and health, population, renewable energy, corporate reform, labor issues, climate change, trade agreements, ethical investing, ecological tax reform, water, and much more. These groups conform to both of Gandhi’s imperatives: Some resist while others create new structures, patterns, and institutions that are humane in scale and nature.

Knowingly or unknowingly, these socially entrepreneurial organizations are informed by Schumacher’s work and depth of humanity. Although uncoordinated and mostly disconnected, the mandates, directives, principals, declarations, and other statements of purpose drafted by these groups are extraordinarily consonant. They are creating conventions and frameworks for civilization that are remarkably in accord with Small is Beautiful. These groups include the International Forum on Globalization, the Grameen Bank, Society for Ecological Restoration, Worldwatch Institute, Friends of the River, Development Alternatives (Delhi), Land Stewardship Council, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, The Just Transition Consortium, The Instituto de Ecologia Politica (Santiago, Chile), American Farmland Trust, The Cenozoic Society, Indigenous Environmental Network, Friends of the Earth, and many more. Never before in history have independent groups from around the world derived frameworks of knowledge that are utterly consonant and in agreement. It is not that they are the same; it is that they do not conflict. This hasn’t happened in politics, not in religion, not in psychology, and not in economics. As worldwide conditions continue to change and worsen socially, environmentally, and politically, organizations working towards sustainability increase, deepen, and multiply. Some day, these dots are going to be connected.

While one might despair that Schumacher’s work has not been more fully taken up by the mainstream economists and educational institutions, I find hope in the work of awakening citizens who are beginning to realize that they must now actively participate to create a world that is worth passing on to the next generation. In this vibrancy and steadfastness, embodied by millions of people working towards a just and humane world, the work and words of Schumacher have been both seed and inspiration. I once had a Buddhist teacher who did not think much about spending one’s life reading books. When asked which books I should read, he replied, “Read the books that save you from reading others.” Small is Beautiful is and has always been one of those rare books –a book that can inform a lifetime.

* (quote provided by Satish Kumar in the 25th anniversary edition of Small is Beautiful)