A Mother’s Recipe for Love

By Fanny Singer

As the daughter of Alice Waters, I am regularly asked what it was like to grow up around such good food. But my childhood was never focused exclusively on what was for dinner (although discussions about meals did populate the intermissions between them); food was a thread embroidering an otherwise richly sensuous upbringing. All aspects of my life were colored by the rhythms of the table, and my awareness of the world broadly spun out from that nexus. In our house, food reified love, just as the changing varieties of lettuce in our ubiquitous salad bowl made the cycles of the seasons plain.

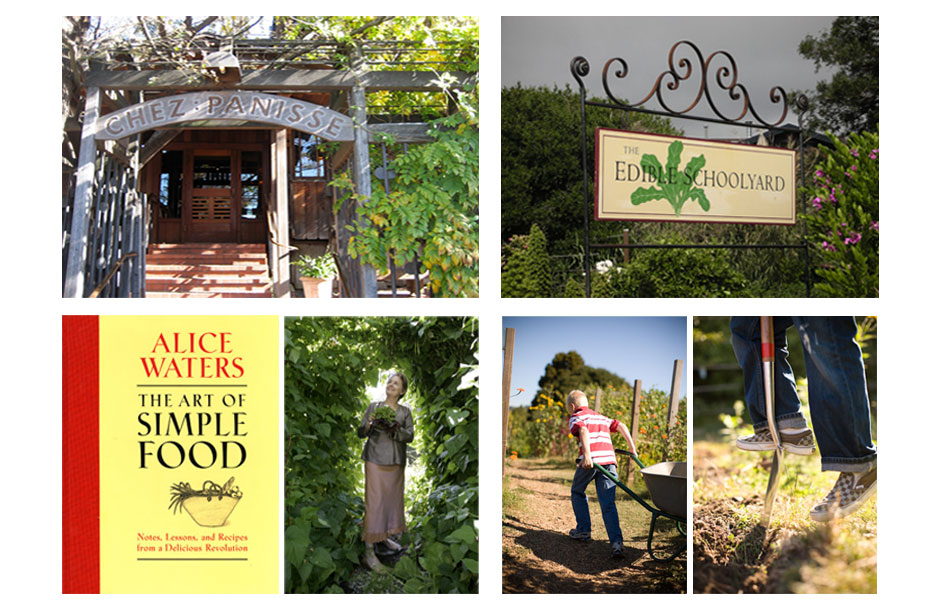

When I was born, my mother had been helming Chez Panisse for over a decade. She had fewer obligations in the kitchen and was free to spend time with me in the evenings. Some days I’d meet her at the restaurant after school, and whirl through the kitchen, where I’d have my fingers decorated with frozen raspberries by the pastry chef-cum-babysitter, Mary Jo, or scramble up and down the back steps with the children of the other cooks. My mother and I would either linger for dinner – during which I would fashion misshapen pizzas under the tutelage of Michele, our Italian pizzaiolo– or we’d do some “Chez Shopping” in the walk-in and retreat home to cook for ourselves.

Though our family ate together virtually every night, meals were never elaborate three-star productions. They were simple and modest, dictated by whatever looked good at the farmers’ market or the local grocery store (which, eventually, my mother strong-armed into carrying exclusively organic produce) or whatever leaves and things were growing in our consistently feral edible garden. My school lunches, which are by now notorious, were something of an obsessive passion of my mother’s. Fairly early in my educational career, intricate, multi-Tupperwared spreads replaced the peanut butter and banana sandwiches that were a fixture of the pre-kindergarten era.

Even after she had lobbied for, and successfully changed, the lunch program at my high school in San Francisco (rescuing it from cellophane-wrapped muffins and installing a talented young cook and an organic salad bar), she persisted in daily packing my lunch. Every morning I boarded a city-bound BART train at 7:06 a.m., meaning lunch had to be assembled in the window after I was roused at 6:00. While showering, I frequently heard the sound of the marble mortar and pestle reverberating through the house, or the staccato of a kitchen knife rapping the butcher block. A garlicky vinaigrette, perhaps? Maybe an aioli? By the time I descended for a hurried but obligatory breakfast, the kitchen would be awash in the warm smells of cooking: a pan-fried chicken breast with sage from the garden, or grilled bread scented with green olive oil; a frenzied array of ingredients spread across the table to be tidied once I was deposited at the station.

It never occurred to my mother that a tender high school freshman might be stigmatized for carrying a briefcase-sized lunchbox to school. Nor did it ever really register with me as an embarrassment, especially not after the first week of school – the amount of time it took for me to develop a reputation for excellence in refection. At lunchtime a covey of girlfriends regularly gathered around to sample garlic bread, sections of blood orange swimming in strawberry-infused fruit juice, or forkfuls of greek salad (dressing always in a separate container to keep leaves from wilting). My lunches might not have made me popular in the conventional sense, but my mother had intuited an absolute truth: good food is irresistible, beautiful and universal.

This is the belief that undergirds all of the work she has done with schoolchildren over the past fifteen years, and which impelled her to found the Edible Schoolyard at Martin Luther King Jr. middle school, just around the corner from our house in Berkeley. The school serves a thousand students, deriving from a broad spectrum of ethnicities and incomes, yet had no cafeteria in which to feed them – until my mother’s intervention. After feats of politicking and urging, and thanks to a foundation conceived for the purpose, a derelict parking lot was transformed into a vibrant and diverse vegetable garden in which the students study, work and eat together weekly. The garden and adjacent ‘Kitchen Classroom’ are now woven into the fabric of the curriculum. What began as an experiment has become an acknowledged methodology in combating childhood obesity, and one that other leaders, from school principals in rural Louisiana to the First Lady of the United States, have adopted with conviction.

When I arrived at Yale, yet again a naive freshman, my mother accompanied me to the dining commons for a welcome meal for parents and students. She was so horrified by the offerings that she resolved immediately to change the food. Two years later, with the help of a student advocacy group called Food from the Earth (of which I was a member), my mother miraculously convinced the administration to surrender a plot of land to a garden and dedicate one of the college dining halls to a pilot program featuring local, seasonal and organic cooking. Over the course of a summer, students labored enthusiastically to transform a section of a grassy arboretum, Farnham Gardens, into a thriving farm. Both the garden and, especially, the Berkeley College dining hall, were so popular amongst students that many were sneaking in to illicitly sample the vastly improved fare. Having moved off-campus by then, I frequented the garden almost daily, practicing my own version of “Chez Shopping” amid tidy rows of tomatoes, beetroot and mizuna. When asked once by a journalist whether deer posed any threat to the garden, the former Yale Sustainable Food Project manager, Josh Viertel, replied: “No, we just have Fanny.”

Now that I live in Cambridge, England, my primary connection to my mother, and to the values of sustainability and locality that she engendered across the United States, is through cooking. Though the King’s College dining hall would certainly benefit from her Midas touch, I have arrived at a place where the mantle must necessarily, for now, be assumed on a micro level: ferreting out organic regional producers, supporting the local farmer who weekly brings his harvest to the Cambridge market square, picking wild nettles for a soup in Trinity College’s crocus-speckled back fields, and most importantly, cooking for friends. Through these cherished acts of conviviality, I know that I am imparting essential values of the table to others, values which will hopefully be carried on in turn.