Exile vs. Miami-Dade County

By Isaiah Thompson

Two signs hover above the desk of South Florida lobbyist Ronald Book. One says “It can be done.” The other: “Nothing is impossible.”

They are mottos: Ronald Book is a man who knows how to make things happen. He’s made a very lucrative career out of it, lobbying the state legislature on behalf of some of the biggest players in Florida, including some two dozen municipalities, among them Miami-Dade county and the City of Miami. His prowess in getting the right ear, making the right contribution, and generally greasing the wheels of state law is the stuff of legend: What Ron Book wants, Ron Book gets.

That’s how it’s supposed to work, anyway. And that’s certainly how it worked when, in 2004, Book began pushing for some of the toughest residency restrictions for sex offenders in the country.

This crusade was personal: after learning that his daughter had been the victim of sexual abuse by the family’s nanny, he made the family tragedy a statewide cause, lobbying first for mandatory HIV testing for convicted sex offenders (he got it), and ultimately for a rule that would raise the state requirement that sex offenders to live 1,000 feet from any school or daycare to 2,500 feet – at that time the farthest restriction in the country.

Again, Book got his way: by 2006, sex offenders were barred from moving within 2,500 feet of any school or daycare in Miami-Dade county.

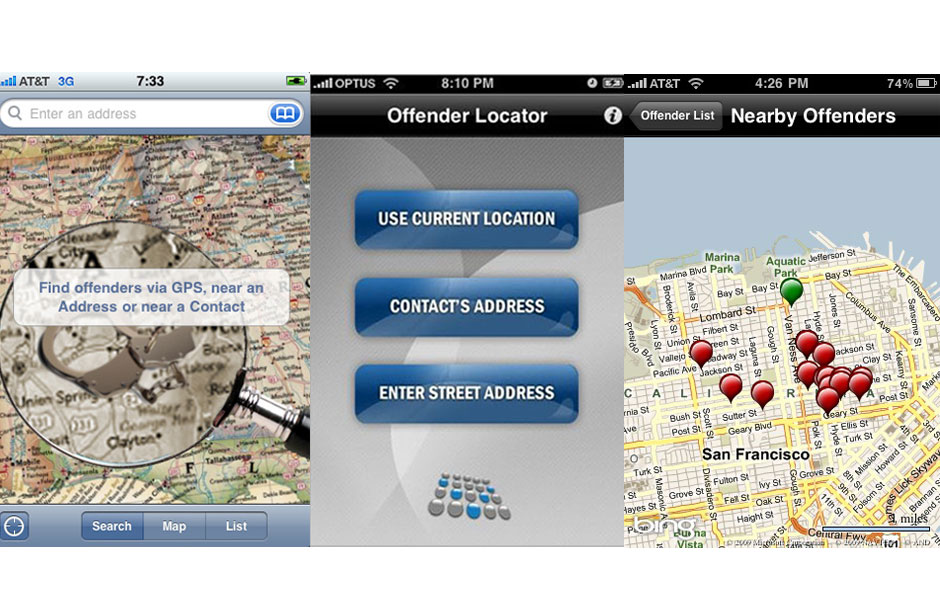

The law had its critics. Civil libertarians questioned its constitutionality. Scholars like Jill Levenson, a professor of human services at Lynn University in Boca Raton, pointed out that there was no evidence that residency restrictions protect children, whatever the distance (most sex crimes are committed by people the children know) – and warned that they might even backfire, causing sex offenders to go underground.

But the law’s proponents would have none of it. If the ordinances made it impossible for sex offenders to live in the county, that was fine with them. If the next county over didn’t want them, Book told reporters, he’d help them draft similar laws as well.

But Book hadn’t, in fact, gotten rid of sex offenders – not by a long shot.

In early 2007, all of four weeks into my first job as a reporter at the Miami New Times –I stumbled upon three men living under a bridge across the street from the county courthouse. They said they were sex offenders – and that they had been sent to live under the bridge by their probation officers.

Each of the men had submitted several addresses to their probation officers upon leaving jail. But each address, it seemed, violated the 2,500-foot rule. And so, a subsequent investigation confirmed, their frustrated probation officers had finally sent them to live under the bridge, the only place they knew of that wasn’t illegal.

The ironies were glaring: By day, they men were free to go anywhere they pleased. It was only between the hours of 10 P.M. and 6 A.M. that they had to be under the bridge, according to the terms of their probation. Their probation officers encouraged them to find work: but mandated they return every night to sleep beneath the bridge.

When the New Times broke the story (and the fact that the bridge was across the street from a rape crisis treatment center for children) the sex offenders were moved – to another bridge: the Julia Tuttle Causeway, which connects the cities of Miami and Miami Beach. An urban desert island, uninhabited and surrounded by water – it was, with respect to the law, anyway – perfect.

And so the number of sex offenders living there grew – first to twenty, when I returned to write another story describing the bridge as a de-facto colony with living structures, a collective kitchen, and a gas-fueled power grid – and then to fifty, and then to numbers that approached 100 people. Many of the bridge’s residents had family members willing to take them in – but they, like most of the population, lived within the 2,500 feet of a school or playground.

It was inevitable that City of Miami leaders began to hear complaints, especially from waterfront condo-dwellers who found themselves suddenly living next to a sex offender colony. City leaders complained in turn to the county government, where officials balked. Rather than overturn the 2,500 foot rule they had passed, they pointed fingers too, at the state’s Department of Corrections, whose officers had come up with the bridge solution in the first place. DoC officials pointed their fingers back at the county’s ordinance.

This July, all the finger-pointing turned to legal action. On July 9, the ACLU filed a suit on behalf of two bridge-dwellers named Elliot Bloom and Brian Exile (the case is called, appropriately enough, Exile vs. Miami-Dade County), alleging that the county’s ordinance is illegal because it’s pre-empted by the state-wide 1,000-foot rule. The next day, the City of Miami sued the state Department of Corrections as well as the Department of Transportation, which oversees the causeway.

The ACLU’s case was rejected in state court; they have appealed and expect a hearing this winter. The city’s case continues to wind its way through the courts.

Ron Book, meanwhile, finds himself in what must be an awkward situation. On the one hand, it was he who pushed so hard for the 2,500-foot rule in the first place. On the other, Book – both as a lobbyist for the city and county and as Chairman of the City of Miami Homeless Trust – is now being asked from all sides to do something about the bridge.

Because Book, after all, knows how to make things happen.

Or does he?

When I returned to Miami in July (I now work for the Philadelphia City Paper), I found Book his usual, confident self – despite a recent Newsweek piece that quoted him saying he had “made a mistake” with the residency restriction.

Book had never said that, he told me. He remained convinced that residency restrictions work – whatever the scholars said. The Department of Corrections had been lazy, he asserted, placing the offenders under the bridge. There were other options, he insisted, and he, Ron Book would find them, just give him “three or four weeks.”

“ I will not rest until the problem is solved,” he promised. “I did not build the reputation that I have in this state by taking ‘no’ as an acceptable standard.”

It will soon be six months since that interview, and some thirty-odd sex offenders remain beneath the Julia Tuttle – fewer, granted, than before. The Florida Department of Corrections has stopped sending newly-released sex offenders under the bridge, referring them instead to the Homeless Trust, which Book chairs. Meanwhile, Book says he’s managed to find housing – within the county – for several dozen former bridge-dwellers.

Book has even declared himself open to revising the 2,500-foot buffer, saying that in “some” municipalities a 2,000- or 1,750-foot buffer might be “appropriate.”

But Book refuses to support a rollback to 1,000 feet – the statewide standard that preceded his involvement – even though his own efforts to re-house the sex offenders are severely limited by the very laws he defends.

While Book’s is correct that there are some places that don’t lie within the 2,500-foot buffer, there aren’t many. Some are so remote from jobs and family that bridge-dwellers would rather stay put. Others are unaffordable.

And those spots that are both affordable and accessible seem to be filling up fast. A records request by ACLU attorney Maria Kayanan, who oversees the group’s lawsuit against the county, revealed that of the 22 sex offenders who had been re-housed as of November 9, more than half were living in just five different locations: five sex offenders had been sent to a single inner-city trailer park.

“ It’s full of kids, and low-income kids at that,” Kayanan says. “It’s quite amazing. They’re just being clustered.”

Book disputes that more than a handful of sex offenders have – or will – be placed in any one location. As for those communities who do end up hosting them: “Four is not thirty,” says Book. “And thirty is not a hundred.”

Even if Book succeeds in re-housing the remaining sex offenders currently under the bridge, it’s hard to see how he’ll do it without concentrating them in a few, mostly poor, areas. Book’s personal motto, “There is a way,” might be right: but maybe that way is backwards.