False Start

By Nicole Davis

Birth is the beginning. The first breath a newborn takes is the start of their life, but in Korea you are born with one year already assigned to your age. And here is the vital difference between two perspectives – two paths being followed by expectant mothers across the world today. This is no longer an east/west divide. Instead, it is the divide between those that address the child’s needs after they are born, and those that begin with conception. Then, of course, there is an immense forest of grey in between.

The journey of motherhood is a very personal one, shaped and distinguished from one another by religion, culture, family tradition, medical presidence, and opinions. Opinions found in the form of “advice”, everywhere from books to videos to birthing gurus. The mothers are young and they are old. Impregnated by mistake or through the aid of science. Some mothers plan every step of their pregnancy meticulously, and others don’t even know they are pregnant until they go into labor.

The journey of gestation till birth, on the other hand, is very universal. Nature has not allowed much room for grey. If a fetus is not viable it will self-abort. If it doesn’t have the right configuration of genetic coding, a healthy womb to implant itself, and if the placenta does not hide the embryo from the attack of the mother’s immune system, the child cannot be born. The journey from conception to breath is always the same length of time (ideally 37-42 weeks). It is all precisely designed. While there is room for some variation – some manipulation – there isn’t very much. However, when it comes to the moment of childbirth, there is a lot of room for variation and deviation from nature’s precise design.

In the United States medically assisted hospital births are the norm, while in Germany a midwife is required by law and a doctor is optional. In Holland an expectant mother without even submitting a request can expect to receive a “kraampakket”, a kit that contains everything needed for a home delivery. The kit does not include painkillers. In Brazil if a mother is from the upper or middle class, an elective C-section allows them to surpass the ails of natural childbirth – an option chosen by over 40% of Brazilian women in the lucky position to make that choice. In China, men are not allowed in the delivery room, that includes male doctors. While the “Bradley Method” of child delivery entrusts the expectant mother’s husband as their sole birth coach. After birth many cultural traditions enforce mother/child bonding. In Japan it is tradition for the mother and child to stay in bed together for 21 days after delivery. In Turkey it’s 20 days, and in Mexico and Columbia it’s a generous 40 days.

There are also dangerous child birthing traditions still continued by cultures across the world that can put both the mother and child at risk. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest birth rates worldwide, and the highest death rates for mothers and children during or immediately following birth, several of these harmful traditions, like vaginal cutting, have come under the fire of human rights organizations. While, on a quieter war front, which began in the late 1930’s, the practices of western childbirth, specifically in the United States, have come under major scrutiny. Joseph Chilton Pearce, an early advocate of natural childbirth, and author of Magical Child (Plume press 1977), wrote, “In America, birth has become a technological, profit-making event. [Where] Pregnancy is quite literally treated as a disease.” (p 47). The resounding solution has been a new wave of birthing practices.

As early as the 1930s, Grantly Dick-Read, a British obstetrician, began to recognize the need to return to “natural childbirth”, a term he coined. In 1942 Dick-Read published a book titled “Childbirth Without Fear”. By naming “fear”, he was able to key into the source of the dilemma facing new mothers today and apparently back then.

Modern and contemporary culture have separated children, and as a result, the adults they would later become, further and further away from nature through the divides created by technology. The innate trust in natural systems has therefore been broken down in our society. The principal behind “natural childbirth” is that every mother is equipped with everything they need to safely and successfully deliver a healthy child. The variables introduced by high-risk pregnancies are always a factor, but the general belief is in the perseverance of nature. Yet, expectant mothers are often plagued by the fear and anxiety that their bodies will fall short of nature. Medically supervised childbirth therefore became the answer to that fear.

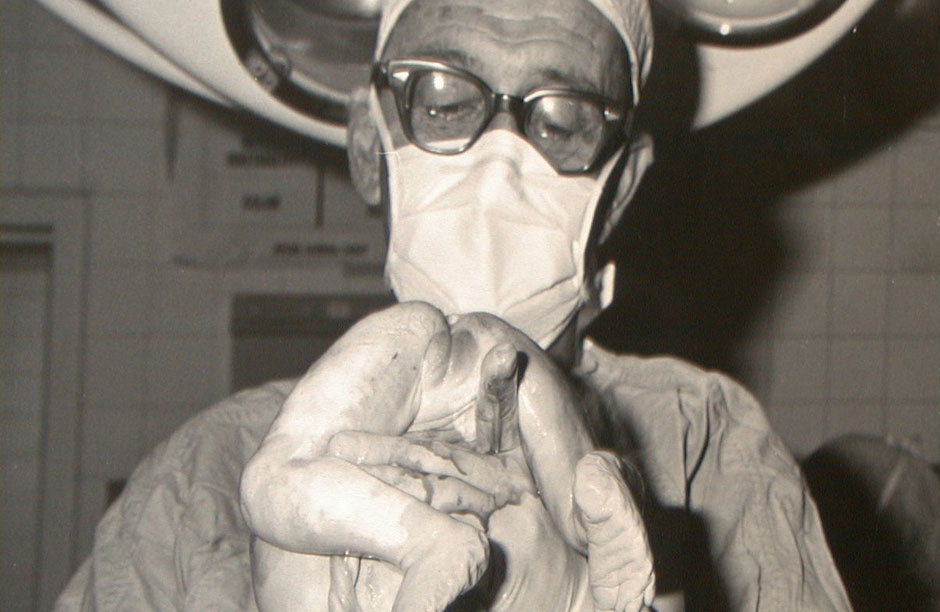

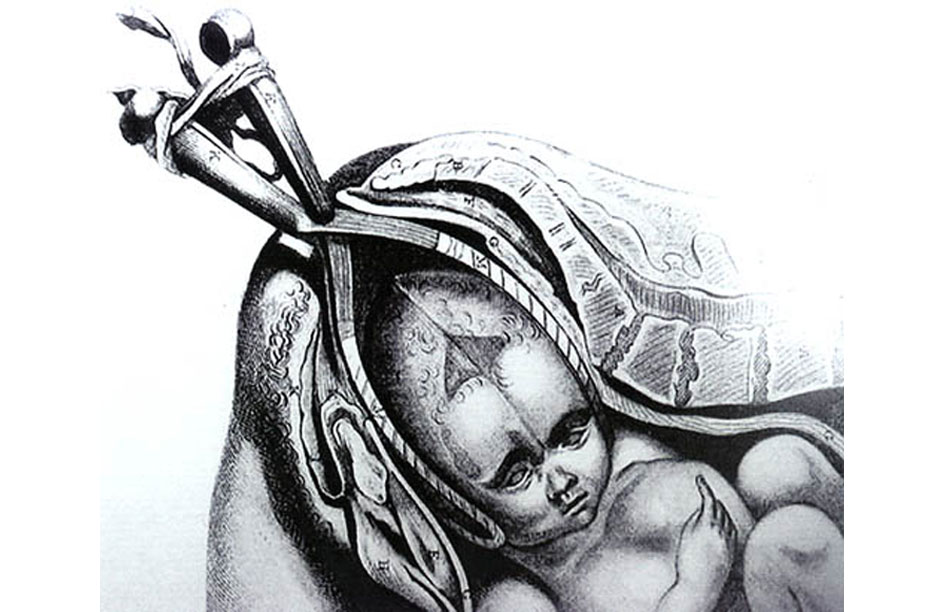

The natural childbirth movement found danger in a few vital and specific practices implemented through the western hospitalized childbirth system. The first being the supine birth position. The debate is that lying on one’s back is the most unnatural and difficult way to deliver a baby. Through the ages women have stood and squatted, utilizing the assistance of gravity and body alignment to ensure the swift and safe passage of the fetus through the birth canal. Since the advantages are clear and obvious, mothers from both the natural birth perspective and medically assisted birth have begun utilizing the age-old position.

The umbilical cord is another important aspect of natural birth. The umbilical cord, which provides oxygen and nutrients to the fetus in vitro for nine months, is equipped with a supply of oxygen-rich blood up to an hour after birth. The theory is that while the baby is transitioning between anaerobic and aerobic breathing, their lungs need a moment to adjust, and the immediate clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord can cause loss of oxygen to the baby’s brain, resulting in minor brain damage. There is also an argument for keeping the umbilical cord in tact until it falls away naturally (approximately 3 days after birth) to maintain the connection between the fetus and the placenta. This is called “Lotus Birth” and is practiced in many natural birth deliveries. The medical argument is that anemia and jaundice can ensue if the umbilical cord is not clamped within three minutes of delivery. This has been proven, but in relatively small numbers and mostly with a benign outcome. However, the hygienic drawbacks, particularly the smell, are a very universal source of aversion towards keeping the placenta and umbilical cord around for more than a few minutes after delivery.

The main difference between natural birth and a medically assisted birth is the abstinence from medicine. The pain of delivery is often too unbearable for expectant mothers, especially those delivering for the first time, making this a hard practice to adopt. The main concern of natural childbirth advocates is the effect of chemicals on the fetus’s brain. The fear is that drugs will obstruct the vital first moments a child has to take in their new world and begin immediately bonding with their mother. These first moments kick-start the development of the infant’s brain and are imperative for the emotional and mental health of the newborn.

This brings us to the greatest argument of natural birth advocates, which is the need to maintain the physical connection between the newborn and its mother. The medical practice of removing the baby from the delivery room for testing and cleaning, and the like, is considered the most detrimental act that can ever occur between a mother and child. “…We must remind ourselves that this infant is highly intelligent, responsive, [and] busily restructuring knowledge, with a brain system five times larger, in size ratio, than his body”, Joseph Chilton Pearce asserts in his book Magical Child. He relates an example that came to his attention through a colleague, Jean MacKeller, who had been working with her husband in rural Ugandan hospitals with Ugandan mothers and their infants. She was baffled by the long lines that would form of mothers and their babies swaddled in simple cloth to their breast with no diapers, yet every single child examined did not have a soiled cloth. She finally asked a few of the mothers how they managed to keep their babies so clean after such long waits. They answered that they would bring their babies to the bushes when they needed to go to the bathroom. She asked how they knew when their babies needed to go. They countered “How do you know when you have to go?!” This is the practical magic of mother/child bonding.

In the United States, the option of natural childbirth gained more following in the liberal atmosphere of the 1960s, and grew into a full blown movement in the United States by the 1970s, culminating with the introduction of water births by French doctor Michel Odent. Today there are no longer two opposing camps. The practices of both have been adopted by new mothers. For instance, a new mother today is very likely to choose a doula (a birth coach) and a midwife and together plan a peaceful home water birth, but all the while keep an Obstetrician-Gynecologist and a hospital of choice on their speed dial as back up. In-hospital birthing centers also offer a fusion of both ideals by offering mothers a lifeline to OB/GYNs and anesthesiologists within the same building that they have created a natural birthing atmosphere with birthing pools, natural lighting, and soft music. It’s the age of pluralism and globalization – it would only make sense that birthing rites would begin to cross-pollinate too.

In order to raise public awareness, the practices of both medically assisted births and natural births should be examined. While studies are vast and varied, the health of children today is undoubtedly threatened by several sources. If there is even a small chance that studies are in fact true, that the very start of each child’s life can effect their development and in effect the rest of their lives, then expectant mothers need to weigh their options. Across the world, expectant mothers face different circumstances, but it is always most baffling to natural birth advocates that the mothers in the country with the greatest opportunity for an optimal birth experience choose what they feel is the less advantageous option for the delivery of their children.

This perspective may be a little too harsh. I was moved when I heard the story of, Michelle Maniaci, a natural birth advocate based in Miami who devotes her life’s work to tuning expectant mothers into the innate power and energy within them – the energy she emphasizes as the energy of the “goddess”. Maniaci leads prenatal and postnatal classes in core movement, prenatal belly dancing, postnatal mother and child bonding through unstructured play and baby massage, and more – all under an umbrella she named “Nurturing Moves”. When Maniaci had her first child, she planned the most perfect home birth complete with a warm scented bath. The day she went into labor, complications arose which required her to be rushed to the hospital for an emergency C-section. Looking back she is able to laugh at the irony, and more importantly embrace the knowledge and power she gained from such an experience, which she has been able to share with her clients. This experience gave her the compassion necessary to relate to expectant mothers coming from a place of fear and anxiety and move them into a place of awareness and trust so that they could set the intention for the most optimal birth, regardless of the specific circumstances and rituals of their actual birth experiences.