Vaccine Report

By Scott Rosenstien

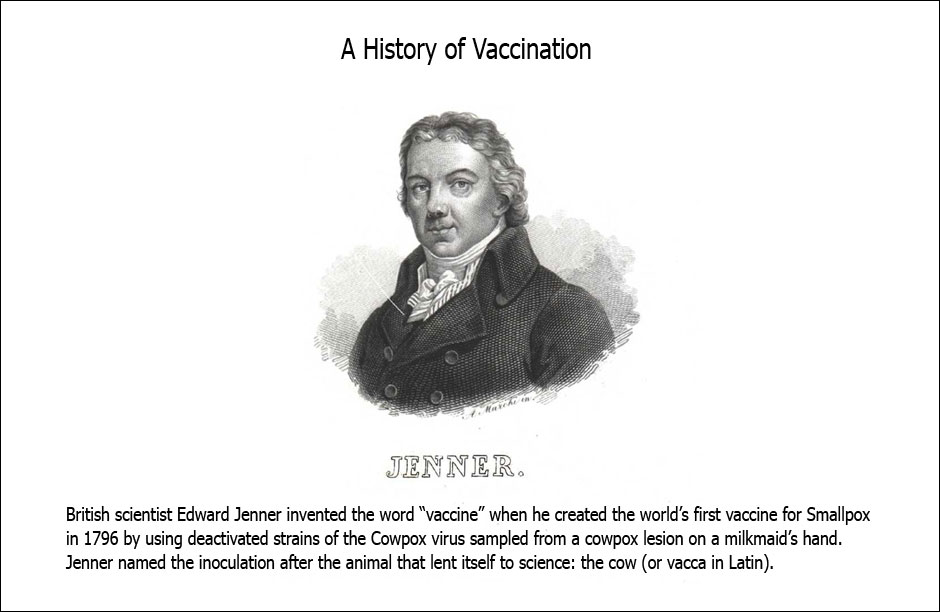

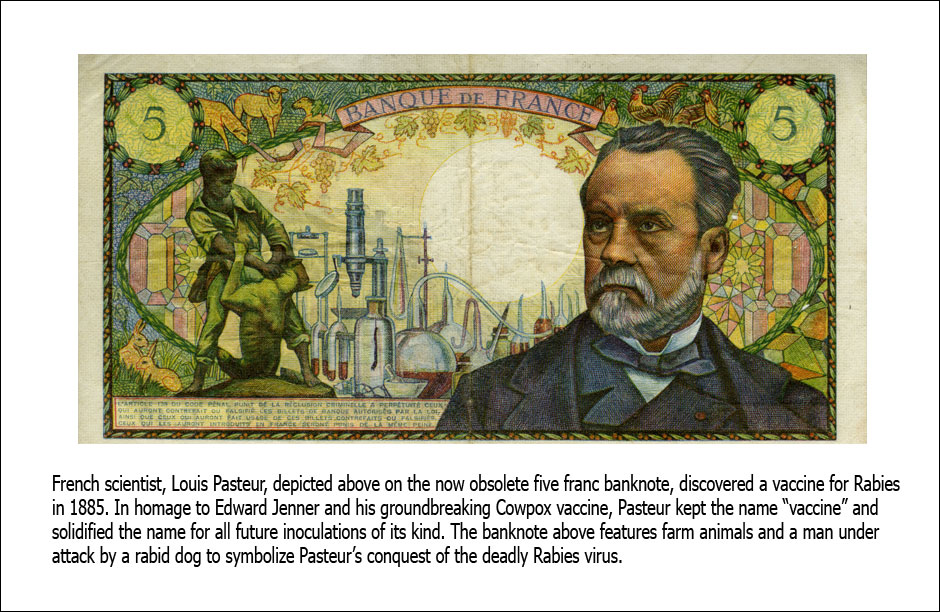

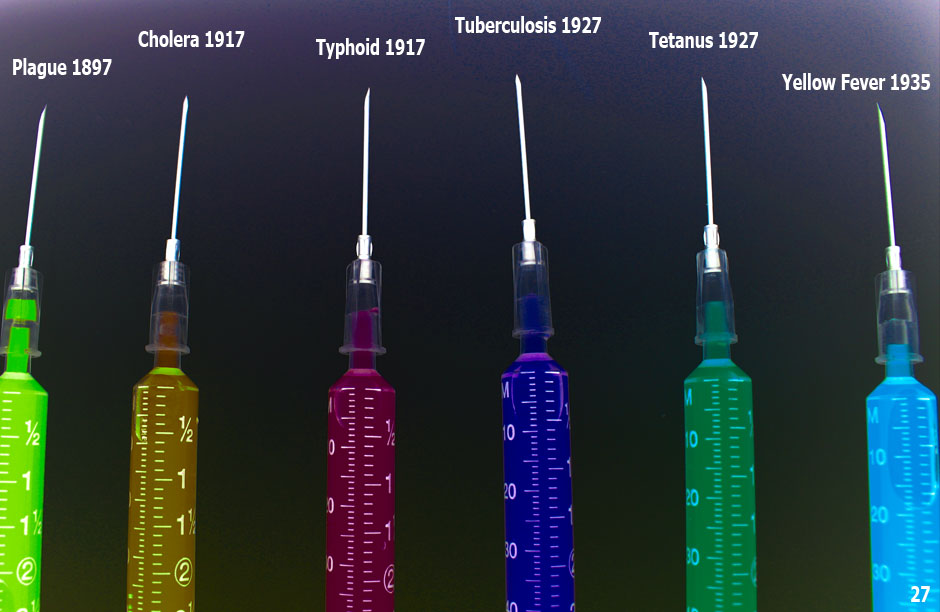

In the developed world, parents are currently deciding whether or not to vaccinate their children against the 2009 influenza A H1N1 virus (typically referred to by the more marketable moniker “swine flu”). Over the past year, the spread of the virus has reached virtually all corners of the earth, but limited supplies and contractual agreements between rich governments and pharmaceutical companies has made the decision to vaccinate essentially a rich parent’s dilemma. And quite a dilemma it has become. A variety of arguments against this vaccine and vaccines in general are currently circulating. These arguments typically range from “vaccines cause autism” to “vaccines implant government controlled microchips into our bodies”. Vaccine skepticism is not new, dating back to the 18th century when the world’s first vaccine against smallpox was invented.

Forgetting for a moment the scant evidence supporting these claims or the dubious websites that sell alternative flu remedies next to their anti-vaccine rhetoric, it is not hard to understand why these claims resonate in middle to upper class neighborhoods across the US and Europe: parents are naturally averse to an activity that may cause undue harm to their children. Making matters worse, many parents rely on the internet for their vaccine information. Since sensational claims and anecdotes tend to dominate Google’s top 10 search results in lieu of more reasonable, empirically based arguments, some parents think that erring on the side of caution and not vaccinating is the best approach. Thanks to successful past vaccination programs, diseases such as rubella, diphtheria, and tetanus are extremely rare in these communities. For now, these parents have the luxury to choose not to vaccinate with very little immediate or apparent downside.

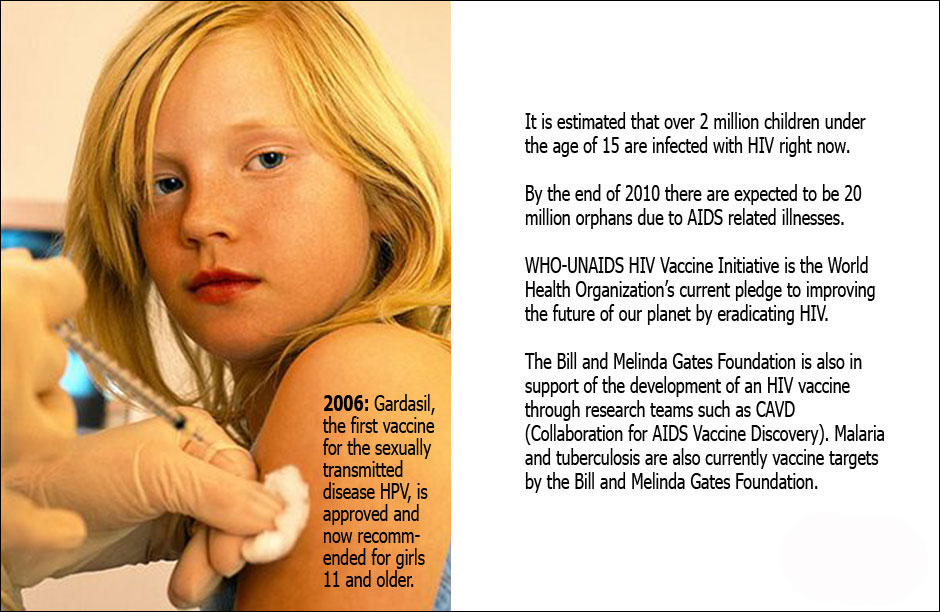

But this luxury is not shared in many low-income countries. The rich/poor country divide could not be more stark: in 2007 measles killed approximately 200,000 people, most of these were children, around 95% in low-income countries. Overall, there are an estimated 2 million deaths each year from vaccine preventable illnesses, the overwhelming majority of which occur in low-income countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Nearly 1.5 million children under age five die of diarrheal diseases a year in developing countries – diarrhea being the second leading cause of death for this age group worldwide. Rotavirus accounts for nearly 500,000 of these deaths a year. In the last few years two vaccines for rotavirus have made it to the market, but to date they are mostly unavailable in the countries they are most needed.

Expanding access to rotavirus vaccine could reap immediate benefits in countries with significant water infrastructure shortfalls that can take several years and a lot of money to overcome. But there are obstacles. The cost of rotavirus vaccines, because they are new to market, is considerably higher than older vaccines and out of reach for most government healthcare systems. While, international aid addressing diarrheal disease pales in comparison to higher profile diseases such as HIV.

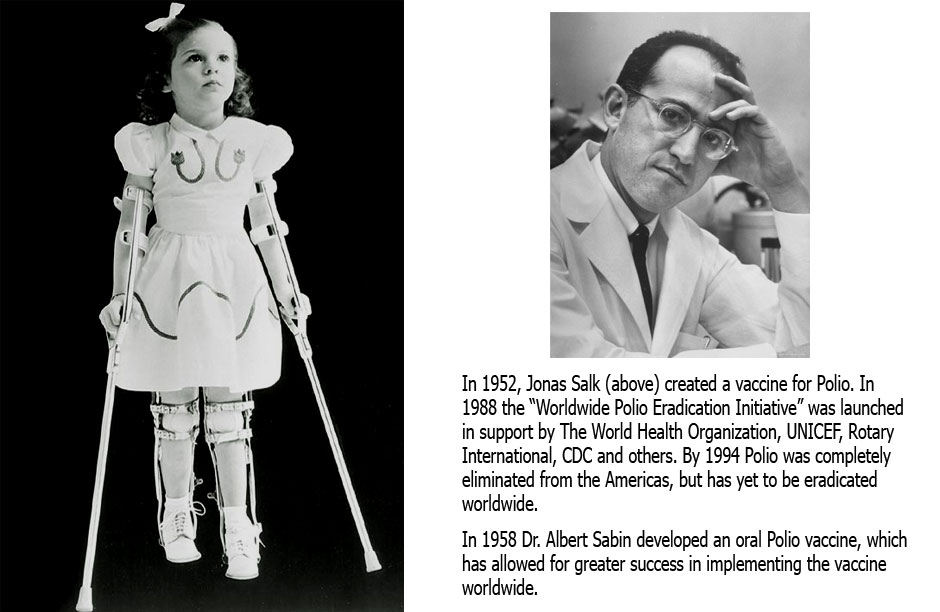

To complicate matters even more, vaccination in the developing world is not without its skeptics. In Nigeria, a group of religious leaders from the predominantly Muslim north halted the polio eradication program in three Nigerian states in 2003, claiming that – depending on who you listened to – the vaccine was a plot from the US and UN to sterilize their children and/or spread AIDS. The result? A rapid rise in polio cases in Nigeria, which spread quickly throughout Africa, the Middle East, and ultimately all the way to Indonesia, producing a devastating setback for the polio vaccination initiative, which was close to achieving its goal of complete global eradication, a feat only achieved once before with smallpox.

Vaccine skepticism in these countries is not terribly surprising. Nigerian officials were quick to question the UN for focusing on polio – a disease that was affecting very few people in 2004 – when measles and diarrheal diseases were killing thousands of children each year. Where were the multi-billion dollar campaigns for those diseases? Also, the reasoning behind the use of the cheaper oral live vaccine was not communicated to the local population. Suspicions were raised when it was revealed that the oral vaccine has been shown to cause polio (roughly once every three million vaccinations). Add to this the US’s not very well received efforts aimed at “family planning” in developing countries and some began to see this vaccination campaign as an attempt to control, not help the people of Nigeria.

To be sure, substantial progress has been made recently, particularly against measles. According to the WHO (World Health Organization) “From 2000 to 2007 about 576 million children who live in high risk countries were vaccinated against the disease. Global measles deaths decreased by 74% during the period.” And rotavirus vaccine access continues to increase, particularly as efforts to bring down vaccine costs through bulk purchasing agreements continue to take hold. Yet, lack of support for vaccination in the developed world represents a significant threat to these efforts in the developing world. Arguably the most successful global health intervention of the last century could easily fall by the wayside if support for this issue buckles under the pressure of anti-vaccine sentiment.

In the developed world, convincing a parent they should sacrifice their child’s well-being for the well-being of the public at large may be a losing battle. To rebuild support for this activity in rich countries and increase the recognition of this issue as a global threat, it should be communicated in a way that adequately portrays the individual risks associated with vaccination vs. non-vaccination. This argument is fairly simple: if these diseases continue to spread in poor countries and vaccination coverage continues to decline in rich countries, it is a near certainty that childhood diseases that were a thing of the past in rich countries will return. Already, isolated outbreaks of measles in the US and UK in recent years have been attributed to poor vaccination coverage. These outbreaks will only grow if this debate continues to be held in the shadow of mistrust and misinformation.