We The Hoarders

By Vicki Raines and Nathaniel Sandler

The United States Federal Government is the single largest buyer of information technology in the world, spending around 80 billion dollars a year. Data has to be catalogued, stored and protected all at an immense cost. The Federal Government currently employs data centers for this purpose – physical locations that contain primarily electronic equipment used for data processing (servers), data storage (storage equipment), and communications (network equipment). In A 2007 report to Congress detailing the extent of these centers and their impact, the Environmental Protection Agency noted that the data center sector consumed 61 billion kilowatt hours at a total cost of $4.5 billion, similar to the amount of electricity consumed by approximately 5.8 million average U.S. households. And that’s just for the storage of our data.

Compulsive hoarding is an affliction with much deeper roots in the American mindset than just the modern collection of digital data. Of late, public fascination with the squalor of hoarding has increased with the popularity of shows like Hoarders on A&E and Hoarding: Buried Alive on TLC. Spend just a few minutes watching these shows and you realize, the profiles of the afflicted are fascinating. You’ll find couches and living rooms buried under years worth of purchased but unworn clothing, kitchens, stovetops, microwaves and freezers full to the brim with all matters of food eaten, unused, and spoiling, and pathways the width of a single person eked out through all of it. Most of the hoarders profiled have reached rock bottom – facing eviction, condemnation, the loss of children to protective services – but as each works with a therapist or organizer to cull usable items and space from the unnecessary they exhibit one deeply recognizable and human trait – the ability to hope in the face of a mountain of trash. Faced with the decision to keep or toss out some supremely superfluous item – a 10th plastic storage box, dozens of used take-out containers – the hoarder will inevitably provide some conceivable future use: “I was thinking I could plant flowers in those, tie some of that sparkly ribbon I got on sale around that stained part and hand them out to friends.” Despite the freak show effect, the shows in simple arc-driven narratives, give us an incredible glimpse into the workings of the American tendency to strive, our relentless quest to make something of ourselves, at once inspiring and insane in its willfulness.

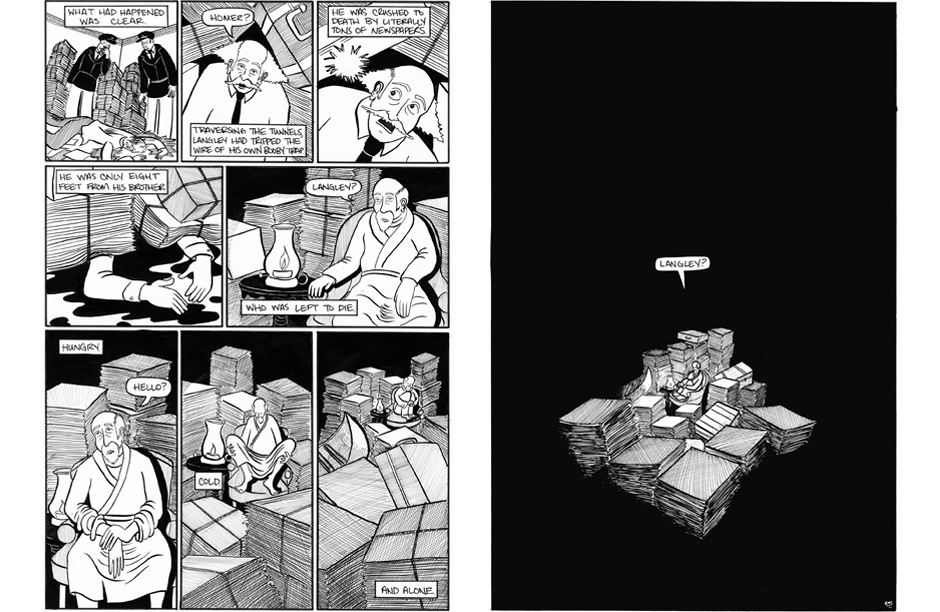

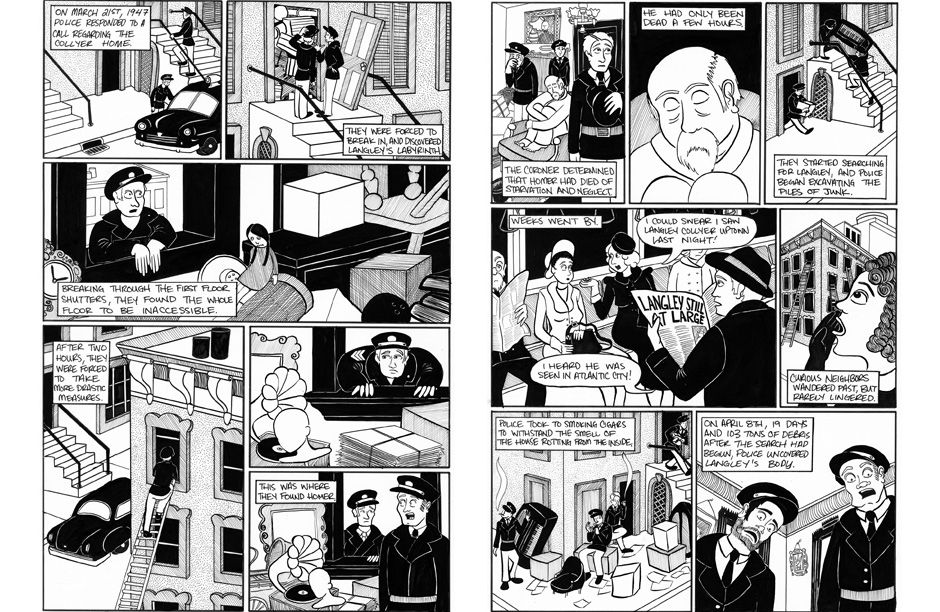

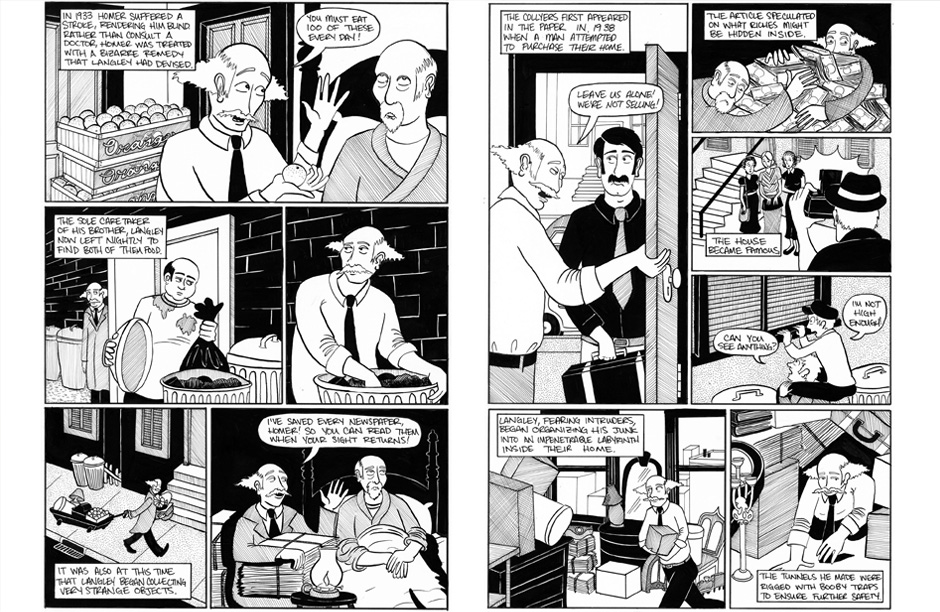

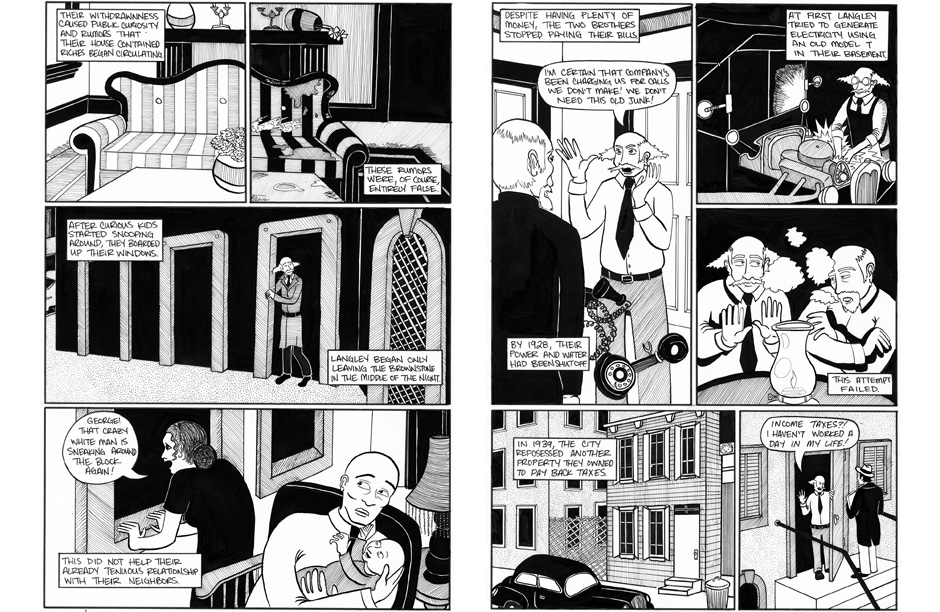

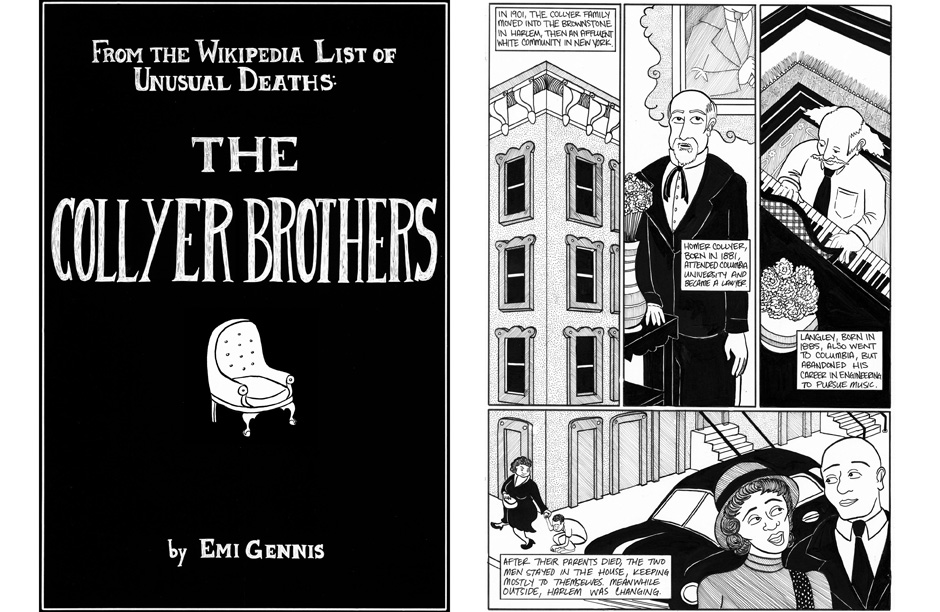

But hoarding has a history in the U.S. well beyond the confines of reality television. For decades we have been fascinated by and romanticized the hoarders among us. E.L. Doctorow’s Homer and Langley, a fictionalized account of the infamous hoarding Collyer brothers of New York City, is just one example. Newspaper and tabloid readers of the 1940’s were entranced by the tales of the brothers’ brownstone after they were found dead among the rubble of their own neurotic collecting. Photos and sordid details were published (130 tons of garbage!), explorations of the home undertaken and theories suggested for the ultimate fate of Homer and Langley. In Doctorow’s telling Langley scarred by the experience of WWI, and Homer, blind and tied to the support of his brother, experience pivotal moments in early 20th century American history from their increasingly shut-off and garbage choked Upper East Side brownstone. All manner of American characters make appearances – black jazz musicians, Italian mobsters, Irish immigrants, and counter-culture hippies – as Homer and Langley attempt to make meaning in an America navigating the devastations of war and depression, political upheaval and cultural change. Both objects and archetypal characters become set pieces. For all the insanity of carting a Model T Ford, 14 pianos, and the daily editions of dozens of newspapers into their home, the brothers’ reasons and theories for doing so remain ultimately human. Indeed the objects begin to take life and meaning when there ultimately is none:

“It was all very eclectic, being a record of sorts of our parents’ travels, and cluttered it might have seemed to outsiders, but it seemed normal and right to us and it was our legacy, Langley’s and mine, this sense of living with things assertively inanimate, and having to walk around them”

Whatever the outcome, the brothers are building an extreme version of the American Dream – for what could be more American than hope, diversity and excessive materialism.

You might say we are all the descendants of Homer and Langely, furiously squirreling away all manner of mp3’s, apps, and digital ephemera. We may even be worse than Homer and Langley; they hoarded in tons, we hoard in terabytes. Consider also the games we play on our computers such as My Life, or The Sims series, where we create and manipulate entire worlds of intangible information, and sometimes even pay money for virtual objects within these worlds. We are all guilty of saving correspondence, photographs, and documents we may never look at again. For all the belief in the power of technology to save us, digital data has just as many negative impacts on the world we live in. For every bit of data we save on our computers and “in the cloud,” some kind of digital machinery must be conjured up to support it. In 1998 there were 431 federal data centers in the U.S. just to support the needs of federal agencies. To match the growth in the storing of digital data, that number has grown to 2,000. Sure, you think, but its all virtual – no problem. One facility run by the Department of Homeland Security in Alabama covers 195,000 square feet, the size of more than three football fields. And all that space takes energy and money to support. While the current administration is taking steps to decrease the number of federal data centers and move toward more efficient technologies to decrease emissions and energy use, the ever increasing use of the internet and America’s dependence on all things digital and virtual might just relegate us to the same fate as Homer and Langley – awash in our own detritus, wondering what we really needed it all for and what it all means.